✏️ Teaching Writing through Transformation (James Moffett on Invention)

What if we start writing all wrong?

Announcements

As I start my third calendar year blogging, January always seems like a slow month. Earlier this week I posted a Note about “ideas marinating in happy things”:

As for my classes, I’ve been moving slowly this balmy January. Before Christmas Break, many students indicated they struggle with vocabulary quizzes because they don’t know how to study. I mean, schools have been force-fed SEL, so go figure, right? So we’ve been learning about study skills and study strategies. (They’ve been rather shocked to learn that multi-tasking doesn’t exist and not all music helps studying!)

We’ve also talked some fundamentals of research. Check out my Note below regarding teaching citations:

So this week I’m serializing another section of “How to Teach Writing Without Curriculum, Part 2.” This week dives into James Moffett and explores his perspective on invention. Eventually I’ll publish the final product, but until then, I wanted to post something.

If you missed last week’s post, here it is:

Teaching Writing through Transformation (James Moffett and Invention)

A composing task that may seem less demanding to an inexperienced writer... is to change a text from one mode of communication or type of discourse to another... (190)

To transform a text is to take the essence of what it expresses and transfer it to another form of writing or to another medium altogether. Dramatizing and performing are transformations of text, discussed in their respective chapters... (165-166)

For students who find so-called creative writing a difficult process, who assert they “have no ideas” or “can’t write,” one process that seems simple enough is to transpose mode, to rewrite into another genre something they have read and liked. For example, a prose fable can be rewritten as a poem, an anecdote as a script, a story as a series of letters, a biography as an autobiography, a diary as a memoir, or a mystery story as a film script. This is a more challenging writing activity than it might first appear. For in changing a selection to another genre you are confronted with the limitations and possibilities of a different point of view, an altered scope, and a new ratio of scene to summary. The students who transpose mode in this way need not be told this; they will discover it as they work. What they learn in changing genre can be transferred to other writing tasks in which they face such decisions as point of view, scope, and the relation of scene to summary... (166)

Of course, rewriting prose or poetry as a script automatically shifts the medium from book to stage, radio, film, or television... (166)

Disclaimer: To my knowledge, James Moffett has been out of print for decades. Thanks to recent efforts by Jonathan M. Marine and Paul Rogers, many of Moffett’s works have generously been made available online through the WAC Clearinghouse. That said, since his physical works are collectors items, I will quote extensively, liberally, and with disregard to scholarly conventions. (This week’s passages remain unavailable without extensive quotations.)

How do you help students who can’t start their writing? What if the best prewriting were actual writing? And what if you improved one medium by practicing another?

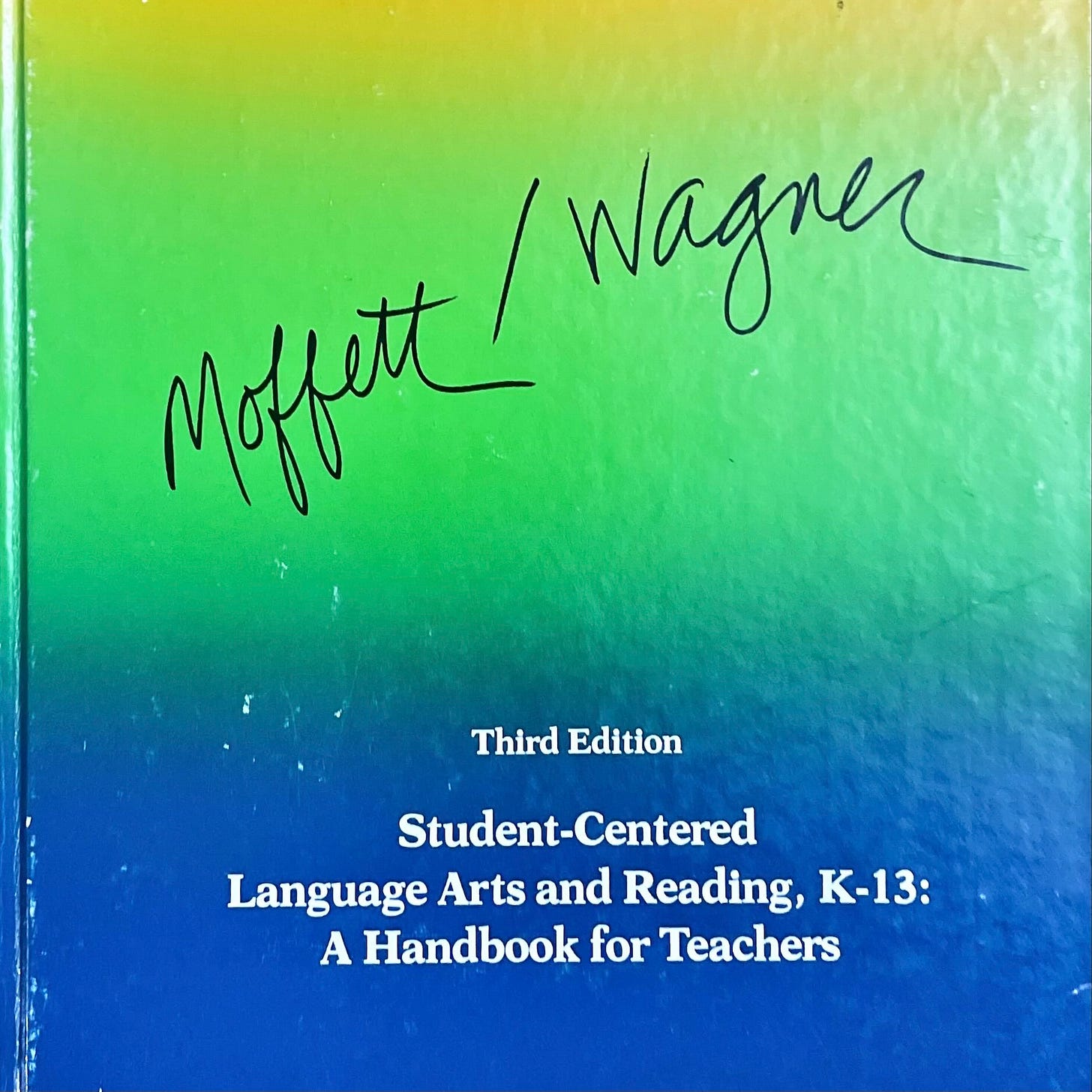

In his book Student-Centered Language Arts and Reading, K-13, third edition, James Moffett presents a fundamentally different approach to invention. Moffett doesn’t just anticipate student difficulties, but he plans for them. His approach offers a subtle yet cosmic difference: moving and transforming one medium to many. In short, he moves from a mono-media approach to a multi-media approach.

Note: For mono-media, I’m operating under the assumption of an essay-only bias. Whether this exists for testing or the guise of academic writing as the only serious writing, the results act the same: A narrow view of the written word.

By moving from one medium to many, Moffett alters both the departure and destination of writing.

Regarding departure, Moffett suggests writing early and starting with familiar mediums. Rather than outline and write about writing (the future tense) Moffett begins with writing (the present tense). Starting with familiar mediums has many implications: One, students write across a variety of mediums. Two, students practice this variety such that they form preferences. Three, students are given choice—at least initially.

Where should students begin? If the destination proves troublesome, then start elsewhere. His suggestions include fables, poems, scripts, stories, letters, biographies, autographies, diaries, memoirs, mysteries, film scripts, and so on. Dramatization adds an additional layer as students embody texts. (This means comprehension through movement.)

Regarding destination, Moffett’s writings provide suggestions for improving essays, but never limit writing to essays only. His initial transformations emphasize differences, not fixed paths. While some mediums flow naturally (diary to memoir), others have starker differences (prose fable to poem). Regardless, nothing prevents writing into essay form.

Transformation drives the process. Shifting mediums isn’t trivial. Every medium has limitations, and shifting across mediums highlights the limitations of both. (How do informal letters differ from formal essays?) Moffett explains how students “need not be told this” (166). While he suggests learning through discovery, I’d caution for discussion instead: My richest classroom conversations have centered around how letters differ from essays.

As he writes, he prefers the verbiage transformation, transposition, and rewriting. Noticeably absent, at least here, includes the word “revision.” Is Moffett against revision? Not at all. He never hesitates to say it elsewhere, but he says it with a key difference: Revision always flows outwards from discussion. Writing isn’t a solitary act. What you change flows from what you discussion. Thus, revision becomes inseparable from community.

Previous Posts about James Moffett

TWT: Let Speaking Teach Writing (James Moffett on Discourse) (2/2025)

TWT: Teach Writing Reactively (James Moffett’s Action Response Model) (5/25/2025)

TWT: How to Teach with Student Writing (6/25/2025)

Transformation always implies transfer. Contrast deepens distinctions. Shifting rule sets requires decisions unseen by the mono-media approach. And unseen does not mean unimportant. These decisions operate above media itself, creating a decision-making meta-layer. (Good luck finding that in state standards!) Whereas mono-media approaches address how and what only, multi-media approaches address why and who.

In practice, asking what an essay is does not answer why you’d write it. Let alone who it’s for. These distinctions matter. Without choice, Moffett might argue, writing reduces to direction following. (By any measure, his “student-centered” classroom borders on anarchy, but I’ll sidestep the issue.) These meta decisions on medium frame conventions themselves. Just reverse the polarity between what and why.

Mediums act like tools, and we should beware Maslow’s Hammers. As writers, we welcome self-imposed limitations as creative freedoms. Self-selection allows you to say, I’m writing this-instead-of-that because. The “because” is crucial. Without building this decision-making meta layer, everything collapses to mono-media. (Or fragmented knowledge at best.) Why write in this media? My teacher told me to, I guess. Why write in that media? Because it fits the situation.

Caution: Be careful with audience, here. Current-Traditional Rhetoric hinges on rhetorical mode. (In The Methodical Memory, Sharon Crowley calls it “EDNA”: exposition, description, narration, and argument.) You can’t directly measure, let alone understand, impact without interviews. Your average standardized test may ask whether an author achieves their purpose, but unless you’re a psychic or fantasy writer, the answer remains unknowable.

What does this look like in action? Don’t let Moffett’s sheer range mystify you. If he started with sixty-four crayons, let’s start with eight, so to speak. Simplify the categories. Picture an everyday problem: How do students write claims with counterclaims? Now picture two unrelated mediums for transformation: from plays to essays. How can drama help essays? Consider how the conventions impact the content.

Writing essays demands fully-formed, interlocking paragraphs. Presenting any view means presenting a claim. This seems not just unconscious, but unidirectional. Students love airing their own opinions. But other views? Counterclaims and rebuttals need conscious effort to move against the current. To mix metaphors, adding other opinions may as well be adding another wing to a house!

Writing scripts demands conversational coherence. While characters literally embody views, talking ebbs and flows through questions and answer. If statements assert, then questions challenge. Without questions, conversations dry up. In everyday speech, focus rarely exists. We clarify points, add evidence retroactively, and venture into tangents. Since people embody views, counterclaims mean good questions.

Drama embodies viewpoints. You either read ‘em like Plato or watch ‘em like Sophocles. Either way, as people act viewpoints, well-placed questions reduce one-sided exposition to leaner exchanges. You say more with less because questions integrate critics. Asking why forces brevity. Besides: Imagining conversations proves less abstract that imagining essays. So start with dramas, explain simply, then upscale to essays.

Mono-media approaches induce blindness and terrible metonymy. Without other mediums, essays lack both the context and contrast to interpret themselves. You can’t understand one medium until you transform it into another. If we write for essays only, essays become the written word. And once you hate essays, you hate writing itself. Sadly, for many students that’s the ever-present reality. The short-term tests matter more than life-long literacy. So pedagogy ages like spoiled milk.

Ultimately, Moffett’s multi-media writing goes far beyond writers block and invention. By operating above medium itself, by moving through transformation, he overcomes the problems of traditional prewriting. In application, the limits exist only with your creativity. Moving from familiar medium to unfamiliar medium and scaling ideas across conventions achieves more than brainstorm, outline, write, revise.

But this almost begs a question: How do we apply this systematically?

Resources (Links)

🎁 New to the blog? Check out my recent starter pack as well as a Google Drive Folder with FREE classroom resources! Also, The Honest School Times has your schooling satire.

⏰ Recent Posts

Why Traditional Prewriting Fails (1/11/2026)

English Has No Super-Structure (James Moffett on English Curriculum) (12/31/2025)

Where AI Fails Analogy Questions (12/28/2025)

Getting Difficult Students to Write (and Other Topics) (12/13/2025)

Where Traditional Writing Instruction Fails (11/28/2025)

My AMLE25 Talk (“Help! I don’t know how to teach writing!”) (11/15/2025)

How to Teach Writing Without Curriculum (1.0) (11/3/2025)

10 Myths about Teaching Writing (10/19/2025)

50 MORE Metaphorical Writing Prompts (10/5/2025)

The Art of the Reading Guide (9/27/2025)

Teach Computer Literacy Before AI (9/13/2025)

The Mysterious Disappearing Analogy Book (9/7/2025)

Templates for Teaching Quotations (8/30/2025)

The Joy of Teaching Siblings (8/24/2025)

How Google Forms Simplifies Data Collection (8/10/2025)

Back to School Night (8/3/2025)

33 Big Ideas to Start Your School Year (7/23/2025)

Teach Computers Before AI: A Sketch (7/21/2025)

Creative Writing Doesn’t Exist (7/17/2025)

How to Teach with Student Writing (6/25/2025)

Practice Writing Rules by Breaking Them (6/21/2025)

🏆 Fan Favorites

✏️ Teach Writing Tomorrow

📓 Other Writing Tricks