✏️ 10 Myths About Teaching Writing (Post #100)

Heed Myth #5 or risk burning out!

Preface and Overture

In November I’ll present my talk “Help! I don’t know how to teach writing!” at the Association for Middle Level Education (AMLE) national conference in Indianapolis. While last year I stood in awe of the Gaylord Opryland Resort in Nashville, this year I’m thankful to present in my own backyard. Without paying for a hotel.

Since my talk has an hour time slot this year, I’m rewriting it from the ground up, integrating posts such as “20 Tips for Teaching Writing Tomorrow“ and “Creative Writing Doesn’t Exist.” I will leave links to the other parts below.

As I write, many areas demand their own posts. (As you read, please comment where you’d like to hear more!) I suppose these other posts will come in due time. And speaking of due time, with a newborn due any day now, my posts might become sporadic for a while.

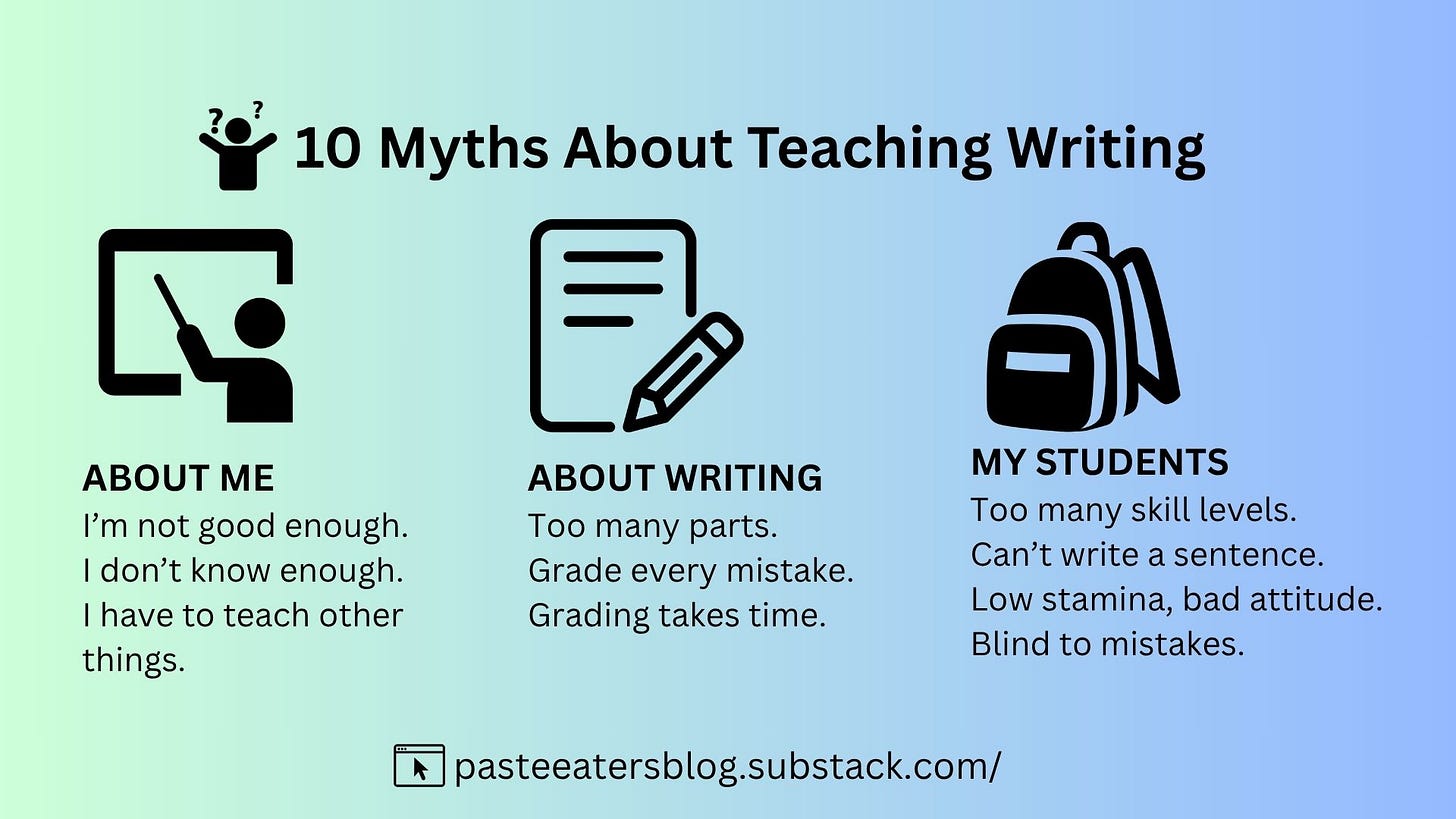

These ten myths cover three major areas: myths about myself, writing, and my students. Each explanation follows a similar pattern: agreeing with concerns, questioning the concerns, and suggesting action steps. This should provide some predictability to reading.

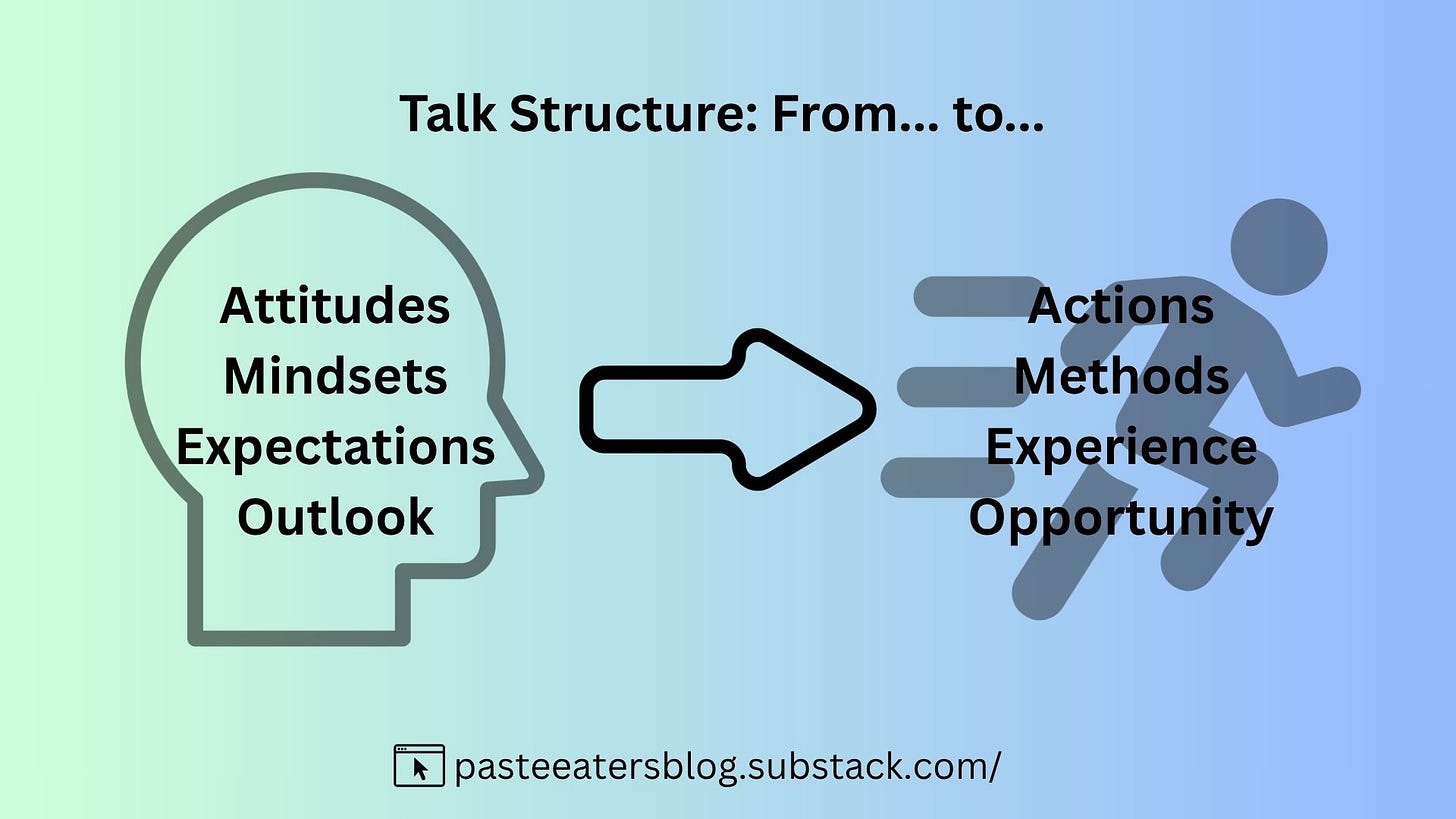

Also, this talk focuses on the why’s before the how’s. Attitudes become actions just as methods become mindsets and expectations become experiences. Any framework requires first principles. And while we can follow actions back to attitudes, addressing these myths help clear the way for a stronger teaching foundation.

The Ten Myths

1. I’m not good at writing myself.

2. I don’t know enough to teach writing. I’m not trained.

3. I can’t teach writing, I have to teach other things.

4. Writing has too many parts.

5. I have to grade every mistake.

6. Grading and feedback take too much time.

7. My students have too many skill levels.

8. My students can’t write a complete sentence.

9. My students have low stamina, bad attitudes, and so on.

10. My students do not see their own mistakes.

Myths 1-3. About Myself

Let’s address these myths head on: It’s hard to teach something you’re not good at. Whether you’re not good at writing, you’re not trained to write, or you feel overwhelmed, the results end the same. If Math operates in black and white, how do you navigate writing, which acts in shades of grey? (Or perhaps worlds of color?)

1. I’m not good at writing myself

Agree: For many, teaching writing is like coaching a sport you’ve never played. Without personal experience, even following steps feels hollow. Without personal experience, teachers need textbooks more than their students. Answer keys help with two-step equations, but not thirty sentence essays.

Questions: When will you be good enough (to teach writing)? What does that look like? And good compared to what—a best-selling author? A fifth grader? Let’s try this: When was the last time you sat down to write?

Action Steps: Apply this thinking elsewhere: Avoid exercise because you’re out of shape. Avoid learning things you don’t know. And so on. This myth has a simple solution: Inertia. Start somewhere. Gain experience. Writing isn’t this formal, unreachable thing. Just put your pen to paper and go. So where do you start?

First, find a blank notebook and fill it. Write before, alongside, and with your students. Build experience with your own tasks. How often do our explanations fail because we won’t attempt our own work? As you grade, grade with notebook in hand. Simply observe. Narrate student mistakes. Aim for twenty statements and twenty questions. Then reflect. You will learn more from your notebooks (at first) than dry, academic texts.

Second, read poetry. When my own creativity wavers, I find inspiration from beauty. I return to the Psalms, Whitman, Dickinson, and lately, James Whitcomb Riley. Poetry does for the ears what art does for the eyes. Lose yourself in something beautiful. Then things happen.

💬 What do you write about? If you need better starters, comment below and I’d love to provide first steps.

2. I don’t know enough. I’m not trained.

Agree: Despite coming from a program that emphasized writing, I had ideals without first steps. This meant years of needless trial and error and failure and frustration. Knowing about isn’t knowing from experience, just as memorizing sports statistics won’t give you a six pack. So what do you do when you start with less than that?

Questions: When will you know enough to teach writing? When does action require perfect knowledge? What if the problem stemmed from lack of experience rather than knowledge alone? What if this could be gained?

Action Steps: Until you manage to memorize an encyclopedia, learn through doing. Allow actions to build the right attitudes inductively. Allow trial and error to teach through experience. Just as there are no perfect people, there’s no perfect way to learn writing or teaching writing. If writing requires revision, the act itself requires constant reflection.

What do those first steps look like? I have so many books to suggest! Writing needn’t be complex or overly formal. What if students wrote an introduction letter that first week? What if they reflected in a paragraph before class discussions? What if they watched a movie clip and transcribed speech?

💬 Would anyone be interested in a writing reading list with helpful books?

3. I can’t teach writing, I have to teach…

I hear this one often: “I can’t teach writing because I have to teach spelling. I can’t teach writing because I have to teach grammar. I can’t teach writing because I have to teach vocabulary.” And so on. Before long, all checkboxes have checks except for writing. However, let me ask:

Questions: When do you use proper spelling? When writing. When do you use proper grammar? When writing. When do you use proper vocabulary? When writing.

Action Steps: Let’s say you have thirty minutes to teach. What if you spent ten for spelling, ten for grammar, and ten for vocabulary? Whoops! No time to write. But what if you spent ten writing, ten discussing, and ten revising? What if your time addressed actual errors instead of hypothetical errors? As the Seven Habits say, start with the big rocks.

If writing feels like one more thing, your philosophy isolates rather than integrates. Covering parts without wholes always adds to zero. Spelling, grammar, and vocabulary only exist with writing. So write first. Start in application and move to revision. Move from wholes to parts. Did I also add it’s less stressful? Check out my posts on teaching with student writing:

Note: While I teach some elements separately, I spend more time in application. Students should read and respond to student writing on a weekly basis.

Myths 4-6. About Writing

So let’s say you’re comfortable writing yourself. Many can write, but not explain. Acting isn’t the problem: Narration is. These next three myths deal in the complexity of writing and the muted silence follows the curse of knowledge.

4. Writing has too many moving parts. (Writing is too complex.)

Agree: I agree here. Writing does have too many parts. Just consider the vocabulary for grammar: There are eight parts of speech, eight kinds of pronouns, and eight examples for intensive and reflexive pronouns. The taxonomy alone fills pages!

Questions: Why does complexity scare us? Does action require naming? Can we work every skill every time? What’s the reasonable limit? Why do student mistakes scare us?

Action Steps: Writing does have too many parts—if we focus on every part at once. Start with wholes before parts. Never place taxonomy before action. You can write a sentence without labeling nouns, fragments, and declarative sentences. Learning taxonomy requires reflection, which means action first.

As with Myth #1, grade with a notebook in hand. On the positive, complexity represents the prescriptive or correct way of writing. On the negative, complexity represents the descriptive or “wrong” ways of writing. So write about mistakes. Immerse yourself in the complexity. Script feedback (whole class explanations). Teach in conversations using student work as the centerpiece.

Once you no longer fear student mistakes as enemies, you can teach them as friends.

5. I have to mark every mistake.

Agree: Stop. Do not attempt this. You cannot sustainably mark every mistake for every student and every paper. You will burn out. You will become a hollow, cynical husk of a human being. This assumption is well-intentioned but destructive. To all.

Question: Has every red mark improved every mistake? Was there a 1:1 relationship? Yes, poor writing deserves poor grades, but what if feedback weren’t time consuming? What if you became more selective with your feedback? What if you only had to draft it once?

Action Steps: You cannot fix every mistake at once. Pick and choose your battles. Make your focus known. Once there, talk more than mark. Red marks may direct the eyes, but without spoken feedback, you’re just coloring. Sadistically. Imagine acting when every step is wrong. You’d give up too, right?

In general, if you write it more than once, write templates instead. Use the 80-20 Rule. For new tasks I grade with notebook in hand and write feedback for the most common mistakes. Later I’ll integrate feedback into assignment sheets and have comments waiting. Every English teacher should know Michael Clay Thompson’s Opus 40 framework for feedback.

6. Grading and feedback take too much time.

Agree: Grading does take time. Consider grading sixty essays at two minutes each: That’s two hours. Since most teachers have more than two classes or sixty students, grading any writing requires weeks of afternoon time. What then?

Questions: How do you grade? What rubrics and mental models? Does the same rubric count for every task? Do you grade the same way every time? What if the rubrics themselves slow you down?

Action Steps: Rubrics act like filters and lenses. Select the right rubric for the occasion. Grid-like rubrics focus on parts only. Grading with microscopes takes forever! But other rubrics consider wholes and allow faster action. You can’t grade every variable, but starting with the big picture and zooming in considers mistakes in context. Check out my comments on grading from AMLE 2024:

Myths 7-10. About My Students

These last myths deal with our students. Because when we’re expected to teach grade level instruction and students arrive two, three, or four years behind, we could spend months off roading just to catch up. How do you start with thirty starting points?

7. My students have too many skill levels.

Agree: Mixed ability classrooms are normal, but large skill gaps mean whiplash. In many cases, gaps matter less than learned helplessness. Some students demand hand holding for every step while others jump through the cracks. Regardless, many teachers struggle here.

Questions: When do we ever get uniform skill classrooms? What if this framing were backwards? What if we always taught individuals, not classes? What frameworks work best?

Action Steps: James Moffett’s action-response model begins in application, teaching descriptively than prescriptively. Rather than pre-teach hypothetical mistakes, he advocates letting student mistakes drive instruction. Begin in reality.

Starting with student mistakes means starting with relevance. Students never have to ask why. As he describes in Teaching the Universe of Discourse, such feedback is “accurate, specific, individual, and timely” (200). Check out my posts on Moffett’s action-response model:

8. My students can’t write a complete sentence.

Agree: Sentence fragments drive everyone crazy. Many English teachers begin with fragments, and despite the worksheets, students still write with them. I’ve heard it many times: “We won’t write a paragraph until they master the sentence.”

Questions: What if fragments represent atrophy? What if students write too little because they write too little? What if quantity leads to quality? What if you integrated writing to explore ideas?

Action Steps: Fix fragments by writing more. Allow writing to explore ideas, serving as more means than ends. So ditch the silly acronyms. Give students the space to breathe and think. Ditch the worksheets, discuss relevant mistakes, and move on. When students write more, they write fewer fragments.

9. My students have low stamina, bad attitudes, and so on.

Action Steps: This myth extends the last. If writing isn’t routine, it’s resisted. So write every day. If they have low stamina, write more. If they have bad attitudes, write more. Since many teachers default to tested writing only—from paragraph acronyms to five-paragraph essays—breaking free solves many problems at once.

Check out my series on daily writing:

10. My students do not see their own mistakes.

Agree: It never fails: The worst writers are the harshest critics. Show them something terrible, and they critique without mercy. Show them their own writing (which is worse) and they just stare and blink. They see everything except for the mirror.

Questions: What if teaching from mistakes and about mistakes were separate things? How do we train students to see their own mistakes?

Action Steps: Here’s a riddle: A room with twenty students has how many graders? If you said one, you’re off by twenty. Feedback isn’t exclusive to teachers. While my students can’t give formal grades, they give feedback. In many respects, I spend more time teaching about incorrect writing than correct writing.

Peer review needn’t be complex. For shorter tasks, fast and focused helps. Partners trade papers for simple point-to mistakes. Simple editing checklists go far. For longer tasks, partners trade and read papers back to their owners. Simply hearing your words in another voice and another cadence reveals mistakes like a flashlight.

Looking Ahead / Further Reading

So where do we go from here? If some attitudes harm teaching writing, what attitudes help teaching writing? Looking to my notes, as I continue to rework my “20 Tips for Teaching Writing” in lieu of other posts, my talk will segue to helpful attitudes.

The back half of my talk will present a working idea: “How to Teach Writing without Curriculum.” I’m really really really jazzed out this one! (I’ve been drafting it since July.) This reworks ideas from my “20 Tips” into an interlocking framework. I’m thinking I could spend the rest of the school year exploring these ideas—drafting the ideals and writing checklist-ready first steps and next steps.

After “How to Teach Writing without Curriculum,” combining posts from the past year might finally start to from the foundation for a novella-sized book about teaching writing. But I don’t want to get ahead of myself. My house is expecting a newborn any day. 👶

Resources

🎁 New to the blog? Check out my recent starter pack as well as a Google Drive Folder with FREE classroom resources! Also, The Honest School Times has your schooling satire.

⏰ Recent Posts

50 MORE Metaphorical Writing Prompts (10/5/2025)

The Art of the Reading Guide (9/27/2025)

Teach Computer Literacy Before AI (9/13/2025)

The Mysterious Disappearing Analogy Book (9/7/2025)

Templates for Teaching Quotations (8/30/2025)

The Joy of Teaching Siblings (8/24/2025)

How Google Forms Simplifies Data Collection (8/10/2025)

Back to School Night (8/3/2025)

33 Big Ideas to Start Your School Year (7/23/2025)

Teach Computers Before AI: A Sketch (7/21/2025)

Creative Writing Doesn’t Exist (7/17/2025)

How to Teach with Student Writing (6/25/2025)

Practice Writing Rules by Breaking Them (6/21/2025)

🏆 Fan Favorites

✏️ Teach Writing Tomorrow

📓 Other Writing Tricks