🖥️ Three Big Benefits to Teaching with Student Writing

Students learn through student writing. So collect and curate it.

Student writing helps students write. Whether you’re learning thesis statements or formal tone, students learn best from other student voices. Teaching without them is like running in total darkness. But here’s the problem: Even expensive textbooks have few teachable examples. So how do you teach with good examples?

Note: This post serves as a follow up to my previous post about Google writing discussions. Check it out below!

The Big Picture. Students learn through student examples. Textbook examples often prove useless. Unlike artificial flavors, which fool through imitation, artificial writing fools through confusion. Logically they may answer the question, but the voice proves fake. Like 80s computer voices. Instead, students need to learn from voices like their own. Teaching writing, therefore, means collecting and curating student writing.

Yes, but. "Don't student examples encourage stealing them? Does giving full responses mean changing your prompts because they know the answers?"

Cheating. Believe it or not, students rarely steal example ideas. Well-written examples give ideas. And trust me, if you’ve read the same essay ten times, you’ll know if students steal.

Changing. Open-ended prompt s sometimes force retiring topics while close-ended prompts do not. For example, after grading thirty "How to Make a PBJ” responses, I retired that topic and it became practice for outlining and critiquing.

Known Answers. I've never been concerned with literature answers being "known." Of course they are! Students can only write and wrestle with ideas after they master basic information. Analysis, then, concerns itself with structuring and interpreting facts.

How To. Collecting student writing takes practice. What method is best? My two cents: Anything which can be copy-pasted. How do you do it? For physical writing, wholesale scanning and typing representative examples helps. For digital writing, file formats which allow copy-pasting text helps, meaning Word docs instead of PDF's.

When Scanning. When scanning student work, consider tagging papers and arranging the best (or worst) examples first. This method takes more time and more file space, but handwritten responses eliminate any interference from the internet.

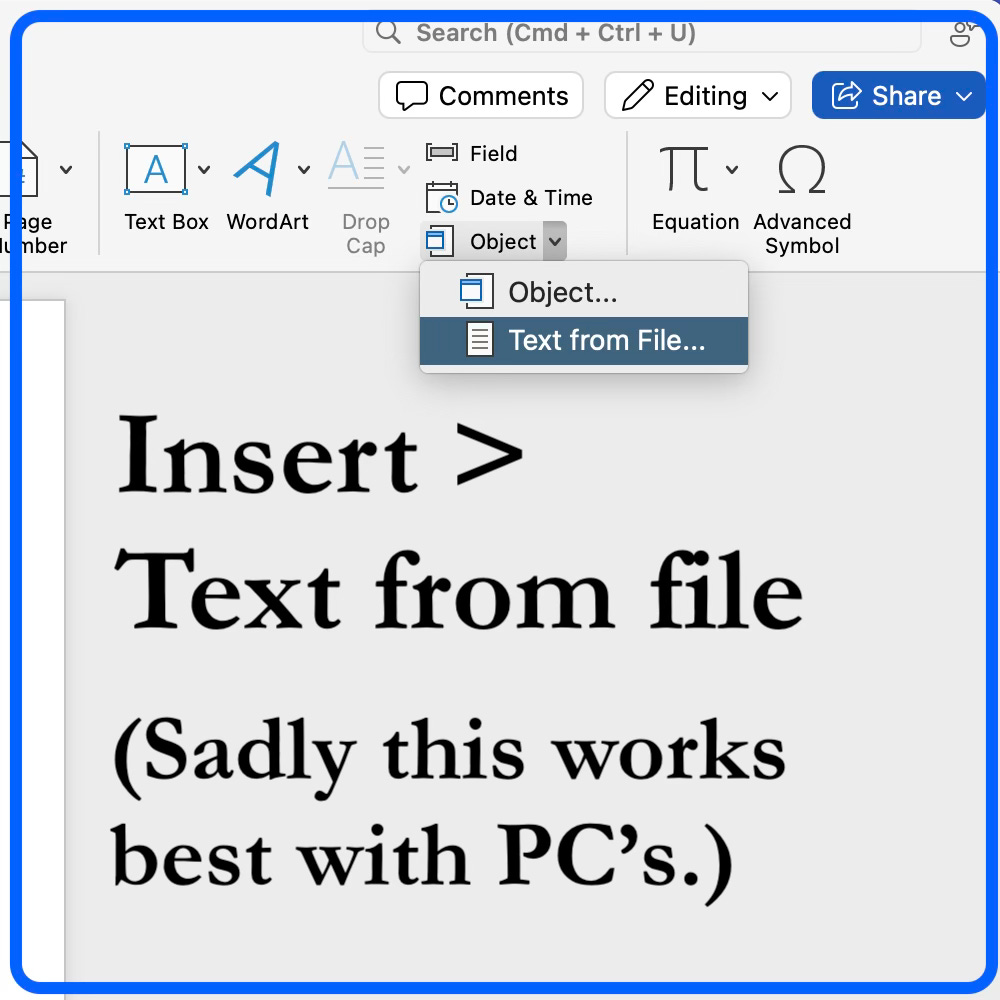

Insert > Text from file. On PCs, Insert Text from file in Microsoft Word allows you to combine scores of files at once. When building work archives, you want one file per assignment instead of dozens per assignment. (Note: For whatever reason, Macs do not allow selecting more than one file at a time, so the feature proves useless.)

Three Big Benefits

1. Examples to study. Teachers should be students of student writing. Why? If we don't study student writing, we'll be perpetually surprised and overwhelmed. Mistakes should neither surprise nor scare us. Imagine if doctors were scared by the common cold!

Teachers should be fluent in all aspects of discourse—from the text itself to what students say about it. Each has value.

However, fluency comes through careful reading and study. For English teachers, student writing is priceless. We should chase it, hoard it, and immerse ourselves in it.

After immersion, interventions become highly specific (yet predictable) tools. Encourage and celebrate mistakes as learning opportunities.

2. More authentic teaching examples. Once you collect and curate student writing, first introduce prompts through examples (answers), then the prompts (questions). Immersing students in student voices adds authenticity and encourages positive risk-taking. Besides, student mistakes create the context for teaching lessons.

James Moffett once described the action-response method (198), where teachers encourage mistakes and teach reactively. Mistakes are good. Mistakes create context for action.

When teaching from a Socratic line of questioning, mistakes become predictable problems for solutions and drive dialogue forward. As Moffett explains, never pre-teach mistakes!

Introduce more abstract ideas with curated student examples and see more engagement. For example, when I introduce thesis statements, I’ll teach through several key mistake types and train them to critique and correct them.

3. Printable and interactive workshops. Curated examples become easy assignments. It’s never just teaching correct ways in the positive, but teaching productive criticism in the negative. (Or positive. Or both?)

After archiving student writing, create simple workshops as next steps. For shorter tasks, consider the Google forms workshop to generate examples. Students read and respond to similar voices.

This goes without saying, but never include student names when using student examples. Also, while some mistakes prove entertaining, being productive means being positive.

Logistically, collecting student writing over one school year should generate sufficient examples for the next. After two or three years of careful collecting, provided varied tasks, you will generate more than you'll ever use. But even then, keep collecting.

Next Steps. I write this post after six or seven years of diligent and at times obsessive archiving. I realize I likely have a fair share of blind spots. The following questions come to mind:

How do you best collect student writing as a habit? How do you collect examples without wasting hours of time?

How do you curate examples and create workshops? What steps do these workshops include and which examples work best?

How do you teach from examples without students fearing they will become the next bad example? (Hint: I create my own fake examples and never let students know which is which.)

✍️ If any of those questions ring a bell, please let me know in the comments section, and I would be more than happy to create more concrete, hands-on posts. Regardless, please let me know what other questions you might have.

📚 While you’re here, check out some other posts:

📱 Also, check out some other posts from my side blog, HappyCasserole.