✏️ How to Teach Writing without Curriculum (1.0)

Programs cost money. First principles are free.

Preface

In November I’ll present my talk “Help! I don’t know how to teach writing!” at the Association for Middle Level Education (AMLE) national conference in Indianapolis. While last year I stood in awe of the Gaylord Opryland Resort in Nashville, this year I’m thankful to present in my own backyard. Without paying for a hotel.

Since my talk has an hour time slot this year, I’m rewriting it from the ground up, integrating posts such as “20 Tips for Teaching Writing Tomorrow“ and “Creative Writing Doesn’t Exist.” I will leave links to the other parts below.

This post covers the back half of my talk. How do you teach writing, I ask? What if you needed principles, not programs? After introducing five basic principles, I’ll discuss implications in a conversational format. I added “1.0” to the title since these thoughts already demand revision. Future posts will explain this thinking in more concrete detail.

Also, I recently posted a survey with a simple question: How do you format your writing assignments? I’d love to trade papers, make notes, and work towards better templates for newer teachers. Feel free to share your favorite writing assignments!

Update: Before I could hit Publish, The Paste Eaters Blog had some wonderful updates behind the scenes!

Programs Over Principles

How do you teach writing? Many wrong ways exist—just see the ten myths. But many correct ways exist as well. The longer I teach, the more I’m convinced that you don’t need expensive curriculum. Or perhaps any curriculum at all. Instead, you need solid first principles. I’ll start with five.

Why these five? Long story short: Every so many years I analyze my teaching by filling pages with statements on the whats, hows, and whys. So I filled pages with statements and reduced to five. These five balance the need for fluency, form, and feedback. Together they form a solid foundation and flexible framework for teaching writing. And did I mention they’re free?

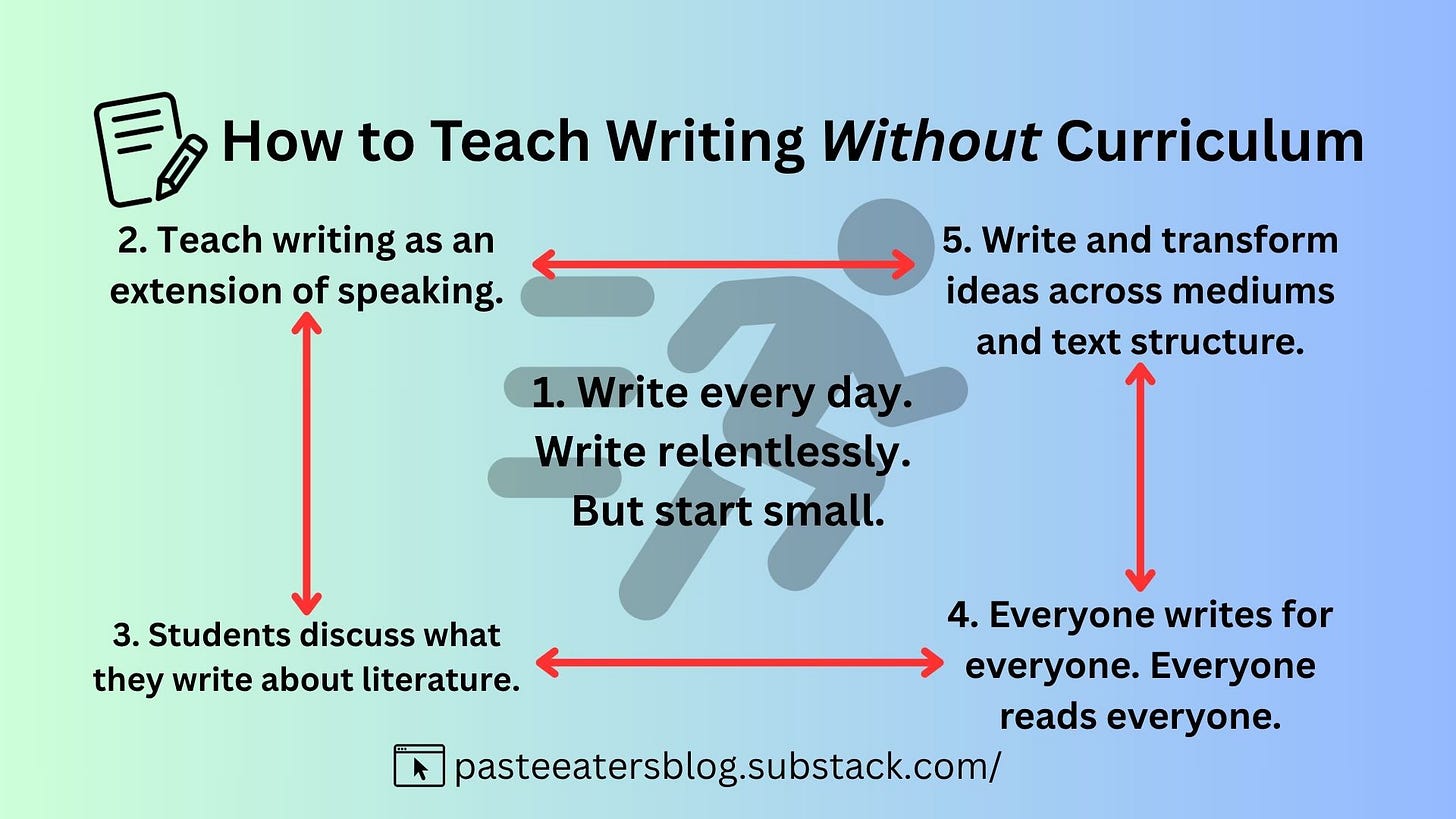

Overview: The Five Principles

1. Write every day. Write relentlessly. But start small. Daily writing builds fluency. Students begin each class by previewing or reviewing topics. Weekly conferences create regular, individual feedback loops.

2. Teach writing as an extension of speaking. Bridging the written and spoken word creates endless (and free) sources.

3. Students will discuss what they write about literature. Integrate rather than isolate. Simplify your teaching by writing about literature. Allow some things to teach other things.

4. Everyone writes for everyone. Everyone reads everyone. Writing is social, not solitary. Conversation creates feedback loops. Write collaboratively with students and use workshops (or public audiences) for feedback.

5. Students will write and transform ideas across text structure and medium. Teach form with text structure and instill flexibility by moving across media.

Introduction: The Five Principles

1. Write every day. Write relentlessly. But start small.

Fluency means your ability to just write. Occasional writing brings occasional results. But regular writing creates regular results. Growth doesn’t require pricey programs, complicated charts, or fancy jargon. It just needs five minutes every class with a pencil, paper, timer, and a good questions.

My students begin each class by writing, either previewing or reviewing a topic. No acronyms needed—just raw, unpolished thinking. We grade them side-by-side in weekly conferences. If they stay on topic and hit the quota, they receive full credit. Mistakes are circled, discussed, and not punished. Why does this work?

Writing is psychology as much as mechanics. Barriers form when students write infrequently and fear mistakes. Barriers fall when student write routinely with feedback. Once writing moves into familiarity and easy feedback, growth happens. So reject expensive programs and embrace the freedom of routine instead. Write every day.

For more, check out my series on daily writing:

2. Teach writing as an extension of speaking.

Writing always encodes speech into something. Yet many classrooms divorce the written and spoken word. Isolation distorts and parts never add up to wholes. Separate topics demand separate lesson plans, and calendars crowd with disjointed topics. Ideas exist as definitions without application.

In practice, the standards-based approach divorces writing from speaking. Writing exists as neither means nor ends. It neither connects nor creates, explores nor explains. Grammar and vocabulary express themselves in the written word, but for many, writing stands as the extra rather than the starting point.

Instead, ground writing in speaking. Integrate speech-oriented mediums like letters, interviews, and scripts. Transcribe speech then change mediums. Allow the spoken word to fill the page. Allow writing to be social, not solitary. Connect the mind, the mouth, and the page. Once the spoken word becomes source, endless opportunities await!

For more, check out my posts on teaching writing as an extension of speaking:

3. Students will discuss what they write about literature.

This view unifies and simplifies. Blend reading, writing, and discussion. Let writing address both content and expression. Rather than plan separate units on writing or grammar, application addresses problems in real time. Revision differentiates at the individual level.

Reading without writing is like inhaling without exhaling. Reading and writing exist like sides of a coin without separation. While talk is cheap, writing is slow. Pencils force contemplation. Writing about reading forces deeper thinking. Discussion further explores those ideas. So discuss what you write about literature.

4. Everyone writes for everyone. Everyone reads everyone.

Many classrooms see students write once and for teachers only. Without dialogue, writing becomes solitary. Without revision, writing becomes disposable. Without feedback, writing becomes stagnant. Without a real audience, writing exists as graphite scratches on paper, lacking the social elements needed for growth.

As teachers, we should write both for and with our students. Modeling, sharing, and collaborating reveal our thinking in real time. Finished products betray process. And goodness, writing is all process! Talking about writing is not the same as writing. Never doubt the power of students watching their teachers stumble and stutter through finding words. Some lessons cannot be scripted.

So write and trade papers. Write in community. When everyone writes for everyone, everyone reads everyone. Dialogue forces feedback as students ask peers to clarify. This simple act drives improvement as audiences expand far beyond the teacher. Social pressures move faster and farther than grades alone.

For more, check out my post on teaching with student writing:

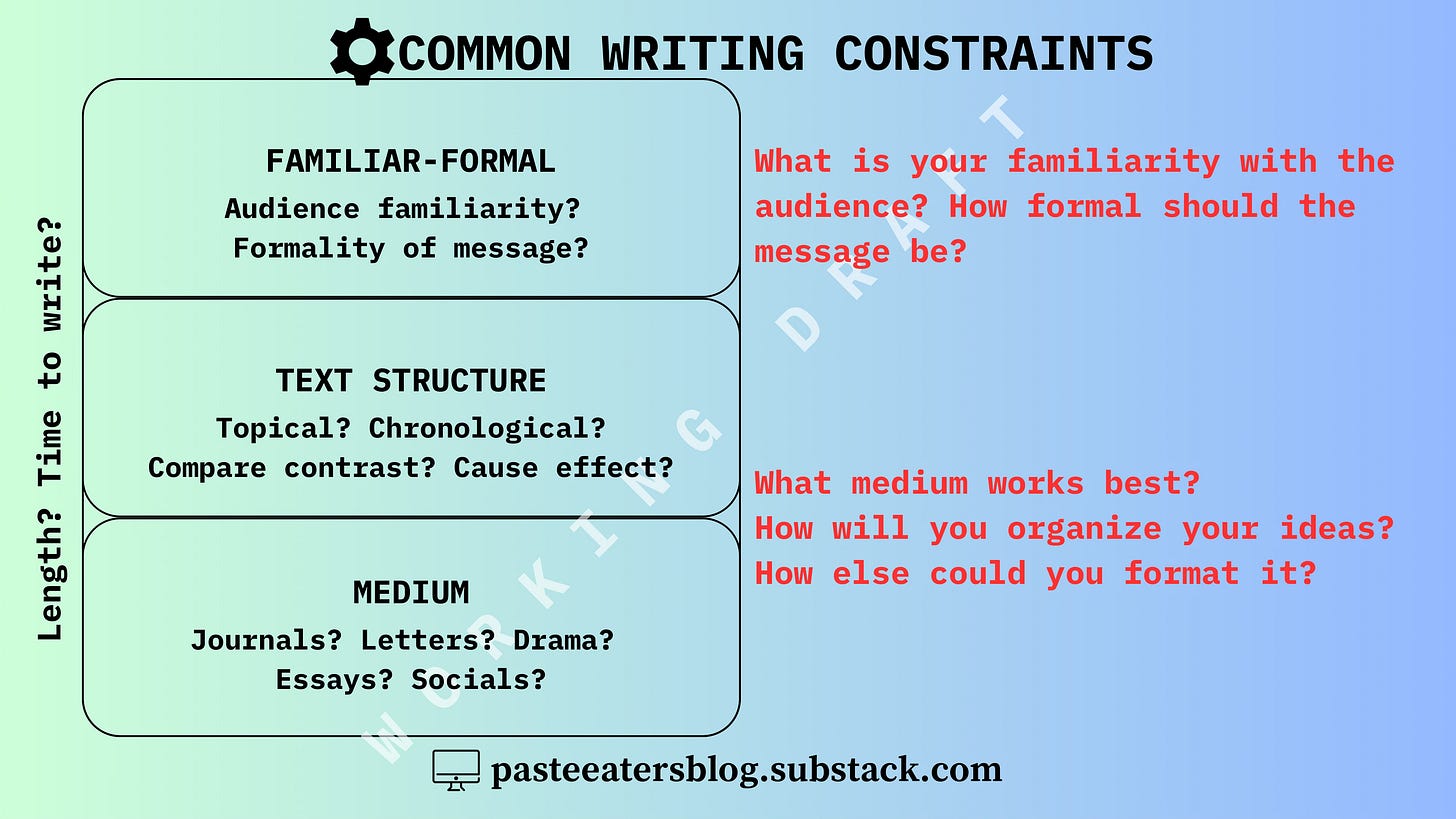

5. Students will write and transform ideas across text structure and medium.

Writing means encoding ideas into mediums. Mediums (as containers) have conventions, but conventions become barriers. Definitions constrain. If the written word exists for five-paragraph thinking only, the written word gains arbitrary barriers.

Transforming ideas across mediums opens breathing room. Skip traditional prewriting entirely. Begin writing with real audiences. So start something persuasive with a letter to a friend who disagrees. Start ideas with interviews where one student talks and another student scribes. Use outlines retroactively (”What did you write?”) rather than starting points (“What could you write?”). From there, move from emails to essays or interviews to letters. Shifting ideas opens many creative possibilities.

Transforming text structures forces other vantage points. Most works contain at least one predominant structure. Exploring other structures enriches thinking. While many arguments begin with lists for and against, why not explore cause and effect as well? Why not begin with a story or chronological account as background? Why not compare related problems and contrasting solutions?

Just remember: Organization is a skill; intention is not. Organization refers to black and white logical sequence. Sequence either matches or not. Details are either chronological or not, comparison or not, sequential or not, and so on. However, intention is not a skill. Despite our best efforts, rhetorical mode (exposition, description, narration, argument) is entirely subjective. We can control sequence but never how our audience will respond.

Together, transforming ideas across mediums and text structure invites a flexible and adaptable approach. This creates not one starting point, but many. Ideally, once students agin experience across media and organization, this creates new outlets to explore ideas. So why not write a summary as a script? Why not begin arguments as interviews (for the other side)? Why not write short monologues that become essays? What do you have to lose?

Principles in Practice (Commentary)

In action, these five principles invite multiple starting points and interpretations. Think webs, not lines. Tested writing only moves one way. By considering dimensions like media and structure, movement opens across all directions. Whereas testing-focused writing ends in five paragraphs, these principles end only by imagination.

That said, if the possibilities ripple outwards, mapping them in depth requires several posts. The questions themselves spill outwards:

How do they work in application? What do frameworks look like?

What do you write about? How do you write every day?

How does teaching across text structure and media work?

Until then, I wanted to conclude by writing conversationally about these topics.

How do these ideas work as a framework? The options themselves sound like many elements to introduce. But think integration, not isolation. Allow some things to teach other things. Movement isn’t always linear. When we write, we encode into something (media). When we write, we favor major sequences over others (organization). Lastly, when we write, we write about something (content).

Thus, all writing has all elements. Mini-lessons help introduce elements, but integration allows reading and writing to work together. Writing across media helps diversify and expand available writing types. Remember: Time not spent writing is time not spent writing. Changing your focus from an essay-first and essay-only mindset broadens and strengthens existing lessons.

What do you write about? Try an easier question: What do you read about? By teaching writing as an extension of speaking, by discussing what you write about literature, everything becomes connected. Integration allows simplicity. Let student mistakes reveal trouble spots, and teach as response.

Together, I suggest writing about books and calendars. Write about school, teenage life, holidays, and changing seasons. Tap into student discussions and occasionally allow student interests to guide. (Well, sometimes at least.) The most important part: Move discussions from the spoken word to the written word and back.

Why focus on writing across media? Few question the test-only mindset. Five-paragraph thinking ignores fundamental aspects of writing. For many, merely questioning this thinking screams insanity. Just like your plates should include more than one food, writing across media provides a healthy academic diet.

⭐️ How do you teach different media? In a perfect year, my classes move from introduction letters to formal emails to transcribing conversations. Each medium includes a mini-lesson, but the discussions compare and contrast the rules across media. And maybe that’s the whole trick: Contrasting forms deepens knowledge each time.

Note: Introducing media requires sequence, but this sequence is flexible rather than fixed. Beyond that, moving between media requires a playfulness forgotten in most classrooms.

Every media has conventions or rules. Conventions define and distinguish. Letters are not essays and essays are not screenplays. This is not bad. Like comparing basketball to baseball or football to track, different games have different rules. Like learning a new sport, until rules become second nature, they remain the first thought. Rules impact working memory, and too many risk cognitive overload.

Some media require more rules than others. The medium may be the message, but the rules of media precede any message. And for many students, a single-media approach requires mastering numerous rules before they’re able to speak. What if a single-media approach forms an insurmountable barrier to entry?

Are you against essays? I’m not against essays: Just essays only. The essay-only mindset creates blindness across other media, as if the written word itself exists for tested writing only. Besides, the essay-only approach (including paragraph acronyms) actively discourages growth. I will die on this hill. Let me explain.

Just compare letters to essays. Letters have few structural parts. They include the date, greeting, body, closing, and signature. The length and formality depend on the audience and purpose. Letters can be intimate or public. In short, letters-as-containers offer nearly unlimited flexibility.

However, even simple MLA essays include multiple layers of fixed rules. The page includes fixed rules on font, size, and spacing along with headers. The structure includes the basic introduction, body, and conclusion with a thesis statement. Formal tone includes lists of formal and non-formal words. Attribution requires in-text citations and works cited pages, sources themselves diverging in formulas. Essays-as-containers offer flexibility in topic, but not form.

Writing a letter requires fewer rules than writing an essay. When we stress essay-first and essay-only, many students worry more about the medium than the message. They begin with cognitive overload and short circuit before their first word. Besides, the essay-only approach discourages exploration. Whereas most know what they’re writing about afterwards, placing medium before message denies exploration to some.

(If students struggle from media, why not intervene? Despite layers of safeguards—MLA templates, checklists, teacher workshops—students still struggle. At this point, assuming students are able, I wonder if the problem requires explicitly creating mental models of the medium. I’ve got ideas and wild eyed intervention ideas, but this might take a chapter to unpack!)

Aside: The invention stage provides no help either. The traditional brainstorm, outline, write, and revise (BOWR) not only places writing last, but provides little space to explore ideas. Thus, some students begin writing as if scaling a vertical wall.

Instead, consider starting with a less rule-heavy medium first. Integrate speaking-centered writing early, such as interviews, letters, and scripts. Allow ideas to form before constraining their form. Allow students the freedom to worry about exploration before worrying about rules. Once ideas have been explored, then upscale ideas to more formal media.

For the college bound, academic writing becomes an art form. But when we worry about academic writing only, we artificially blind their thinking. If creativity requires questioning boundaries, then students begin in straitjackets. Five-paragraph thinking becomes Maslow’s Hammer where everything else becomes a nail.

So do your students only write in letters, scripts, and essays? Not always. Before longer writings my students write daily journals, answer reading guides, write questions about reading, and complete graphic organizers. Writing no doubt helps process information, but unless students have a basic understanding of basic facts, then factually incorrect writing helps nobody.

From a practical standpoint, writing varies with regularity. Students have daily writing (journals), mid-length writing (quizzes and other media), and periodic longer writing (end of novel essays). Sometimes journals chunk topics across days, and oftentimes journals and quizzes connect towards longer essays. Time allows depth across repetitions.

Ultimately, students write in progressions, moving from one activity to another.

Until Next Time / Writing Progressions

Can you give ideas for moving between media? You know, I thought you’d never ask! But as I type, my word count has exploded far beyond my first intentions. In allowing this second half to grow like vines, I recognize it will eventually need revised. So until then, I want to save some progressions and transformations for their own follow up post.

💬 In the meantime, feel free to drop questions below. I’m sure I missed some obvious things.

Resources (Links)

🎁 New to the blog? Check out my recent starter pack as well as a Google Drive Folder with FREE classroom resources! Also, The Honest School Times has your schooling satire.

⏰ Recent Posts

10 Myths about Teaching Writing (10/19/2025)

50 MORE Metaphorical Writing Prompts (10/5/2025)

The Art of the Reading Guide (9/27/2025)

Teach Computer Literacy Before AI (9/13/2025)

The Mysterious Disappearing Analogy Book (9/7/2025)

Templates for Teaching Quotations (8/30/2025)

The Joy of Teaching Siblings (8/24/2025)

How Google Forms Simplifies Data Collection (8/10/2025)

Back to School Night (8/3/2025)

33 Big Ideas to Start Your School Year (7/23/2025)

Teach Computers Before AI: A Sketch (7/21/2025)

Creative Writing Doesn’t Exist (7/17/2025)

How to Teach with Student Writing (6/25/2025)

Practice Writing Rules by Breaking Them (6/21/2025)

🏆 Fan Favorites

✏️ Teach Writing Tomorrow

📓 Other Writing Tricks