✏️ How to Lesson Plan Once (And Never Again)

The thought experiment which transformed my first year of teaching.

Teach Writing Tomorrow addresses major myths and misconceptions about teaching writing. It will move from attitudes to actions and mindset to methods, showing how any teacher, regardless of their own perceived ability or creativity, can teach writing tomorrow.

Last Time: Teaching & Habitual Re-Creation

My first year of teaching began with a creativity crisis: I was boring. Students openly complained about doing the same activities over and over. The worst part? It wasn't for lack of effort—or materials—on my part. While many books cover content, teaching, and teaching content, few model teaching content. Few model actual lesson plans. I'd spend untold hours habitually re-creating the same activities. I needed a creative jolt, but couldn't find solutions in conventional materials.

III. The Thought Experiment (Part 1)

Months later, as December dawned, I grew more desperate. Still boring. Just months earlier, as my teaching program ended, I felt like I could do anything. Now, I could do nothing. And certainly nothing right. I just needed examples.

This time I stared at a blank notebook page, determined to solve this problem. My brain was swimming in a chaotic and combustible mix. Something was on the tip of my tongue, but I wasn't sure what. If I struggled lesson planning so much, what if I lesson planned once and never again?

What a stupid question! Then again, why not?

Exasperated, I scrawled the question across a blank page: What if I listen planned once and never again?

Before starting in earnest, I wanted to walk around the problem.

How did I define my terms? What is a lesson plan? I began by rejecting the stereotypical fifteen page lesson plan from teaching programs. Useless. (Try that for 180 days...) Instead, zooming in and out, I framed it through travel: A syllabus acts like a calendar and lesson plans act like itineraries. Once you have general direction, lesson plans use schedules to sequence activities.

And perhaps itineraries worked like recipes—from packing lists and times to ingredients and steps.

How much do teachers plan for? Let’s approximate with some back of the envelope figures. Seven hours per day over 180 days means 1,260 hours or 52.5 days. Over thirty years, a full career, that’s 37,800 hours or 1,575 days. (Or 4.31 years.) Just three teaching activities per day for 180 days means 540 activities. Over thirty years that’s 16,200 activities.

What’s the most inefficient planning possible? If teaching is performing, then scripting every line minute by minute seems obvious. Since we take longer to write sentences than to speak them, scripting an hour of teaching would take more than an hour. So no scripting.

Note: Many years later I would begin scripting important lessons, comparing my dialogue to student results, input and output, before and after, cause and effect. But that's another story.

How does that work as information? Well, information is either new or review, presented or practiced. When I started teaching, the “flipped classroom” was all the rage. So this had me thinking: Information was experienced either in the classroom or at home. These in mind, I sketched a simple grid with PRESENT x PRACTICE and IN x OUT (of school) to get the following.

Figure 1. Activity x Location

These four categories represented the scope of planning. Present-In means covering new information in class while Practice-In means practicing old information in class. Present-Out means learning new information at home while Practice-Out means homework. Where was my focus? With some homework, balancing Present-Out and Practice-In. Maybe. This wasn’t anything earth-shattering, but I needed some sort of starting point.

Where do teaching books fail? Many function as encyclopedias rather than how to's. I could name activities, but only in disconnection. I knew whats without whens, wheres, and hows. So what did I know? Some activities worked early in teaching (entrance tickets), some worked late in teaching (exit tickets), and others fell in between. This in mind, I sketched four time blocks—before, during, after, and any. Then I started sorting.

Figure 2: Activity x Time Index (General to Specific)

The problem still remained: I lacked mental models. But a functional index helped, expanding whats to whens. I felt more confident with my materials. Sorting by time not only made my entire teaching library accessible, but I realized I could read from left to right with writing activities. Could that be useful? What if planning functioned as connecting?

How do veterans approach planning? I reflected on past conversations. Some teachers scratch the daily topic in a blank book and just teach. Others write detailed plans year after year, filling shelves with binders. Everyone else falls between extremes. Each group started from precedent, but while some relied on internal memory, others externalized it. And if the best activities moved forward year after year, precedent meant patterns.

New teachers can’t begin with experience. But what if they did? Browsing through binders would save years of creation. Instead, teachers could begin by selecting options and gaining experience from them—like following a cookbook. Starting from someone else's precedent was still precedent. Context, though, served the limiting factor. Why those lesson plans? When were they used? Who were they for? How were they received? How do teachers change?

I wondered: If we account for teaching styles and similar lessons, could these volumes simplify to pages? It’s unlikely each binder featured 180 unique lesson plans year after year. Since plans reduce to activity sequences, surely teachers favored some means of presenting and practicing information. Applying the 80-20 Rule or Pareto principle ensures that a handful of patterns repeat over time.

As I visualized sifting through binder after binder, I wondered: What if decades of plans reduced to fifteen pages? Or less than ten? Working backwards, could the right questions produce them a priori? If so, what mental steps do we follow to plan? It’s all assembling information, right?

Let's start with that ending point, I figured. How else does planning work as information?

First, English does English things, Math does Math things, Science does Science things, and so on. While some activities should be universal, not every activity is. Science performs labs and Band performs musical instruments. Yet overall, every subject contains predictable, subject-specific activities.

Second, let’s pretend we read a short story. We might read it, discuss it, and write about it. Cool. That particular order means a specific “lesson plan.” But if we mixed the steps, that variation becomes a different specific lesson plan. Cool. However, if we switch out the story and kept the same activities—or variations—those became new lesson plans.

Therefore, from an informational standpoint, I formulated the following statements:

1. All subjects have fairly predictable, content-specific activities.

2. Lesson plans sequence activities for given content. Two things follow:

3a. The same steps often recycle for different content. (Same steps, different stuff.)

3b. Different sequences become different lesson plans. (Different steps, same stuff.)

I circled back: What if I could lesson plan once and never again? Would I really need 180 unique lesson plans? Likely not. Likely far less.

IV. The Thought Experiment (Part 2)

Now that I had a more solid foundation, I began meditating on the mental and mechanical steps of planning. The questions just spilled out: How did I plan? What steps did I follow? What steps consumed the most time? As input-output, why did I keep creating the same plans? Could charting my steps help chart new steps?

How do you lesson plan once? I let metacognition become mirror. Once I knew the daily topic, I imagined reaching into my mind and grasping for relevant activities. This meant finding one from all, one from many. Once I had that activity, I held it and repeated the process several times. Once I held around three activities, I toyed with variations and selected the best one.

Imagine planning as a card game: I'd recall the deck then retrieve relevant cards. Once I had three cards, I'd toy with variations, each sequence or hand representing a distinct "lesson plan." Yet recalling alone destroyed my mental energy. Even then, I'd forget cards and habitually re-create the same hand week after week with diminishing returns.

So which mental step took the most effort? Recall. I knew teaching activities but forgot them. My limited recall therefore had limited results. So if recall consumed the most time, I transformed the step into a writing activity: Name every teaching activity you know.

And so I scrawled, scribbled, and scratched. While the original paper has been lost to time, the activity inscribed itself to memory:

reading as a class

instant drafts

reading in partners

writing

KWL (Know, Want to Know, Learned)

entrance tickets

exit tickets

Socratic-Fishbowl Discussions

Sustained Silent Reading

partner writing

brainstorming

partner brainstorming

group reading

And on and on and on it went. Activity followed activity as a list emerged, growing like an unwieldy vine. But unwieldy became useless. This wasn't it. It was too messy to be useful.

Studying the list, I realized each activity shared similarities (dimensions). One, most activities had James Moffett's four Language Arts—reading, writing, speaking, and listening. (I blended the last two as "discussion.") Two, each activity scaled by people: working alone, in partners or groups, whole class, and teacher-led. (I ignored the time or when with this list.)

So I drew two axes, activity and person, resulting in twelve categories. For example, students could write alone, with partners-groups, or as a class. But not every category worked. For instance how can students Discuss-Alone? Through personal reflection? Also, any Teacher-Led activity means modeling. (Or just a “Lesson”?)

Figure 3a. Activity x Person (General)

Moving from general to specific, each category represented scores of specific activities. Partner Discussions meant Turn and Talks, Think-Pair-Shares, and even Peer Review. (Peer Review combines Writing and Discussion.) Writing-Alone meant reflecting, brainstorming, instant drafts, KWL's, and so on. The possibilities were endless! So I could either translate and transfer my unwieldy list into an organized chart or stay general with the category names. (I chose somewhere between.)

Figure 3b. Activity-Person Schema (Even More Specific)

Aside: Have you considered Acting as a category? Embodied cognition represents a vast, untapped continent. This morphs my categories from twelve to sixteen. Reading getting stale? Transform novels into scripts. Try having students read as characters with a narrator. Or perhaps try students staging scenes, transforming the verbal to the visual. Embody reading comprehension. Never be afraid to use your imagination. It beats boredom!

Since this chart visualized recall without mental effort, what now?

Sequencing follows recall. Combining now served as step one—not recall. So this meant a new starting point as my mental effort shifted forward. Eliminating recall and subsequently forgetting felt revelatory! What possibilities! The blank page felt like a vast expanse. So I started combining, slowly and blindly at first, then with growing speed until I scribbled furiously across the page. The expanse shrunk.

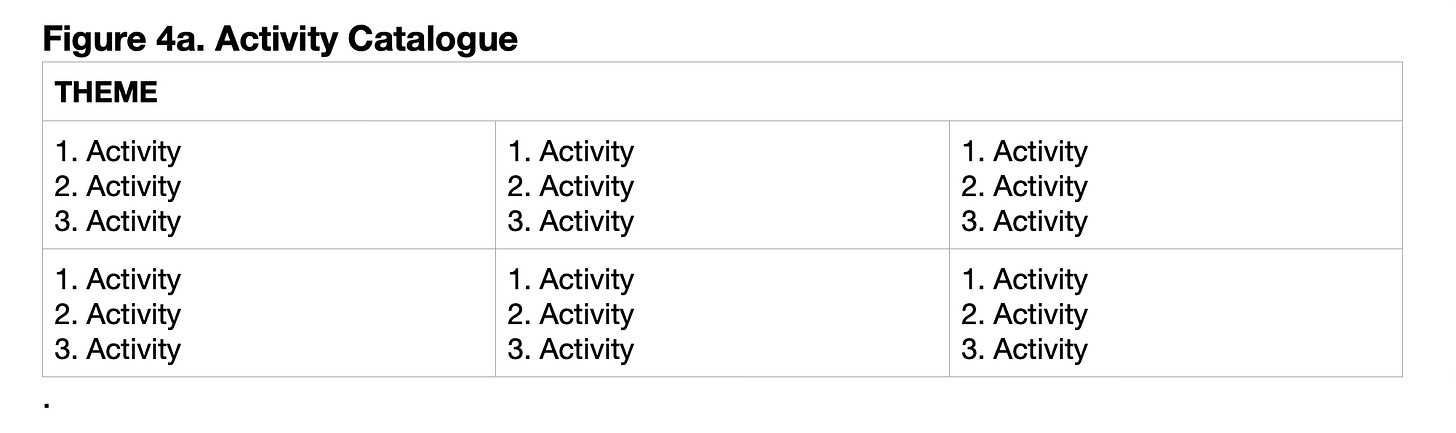

Figure 4a. Activity Catalogue

As I combined, options begat variations. It felt like gazing into a moving kaleidoscope. Within a half hour, as combinations grew, a familiar problem emerged: organization.

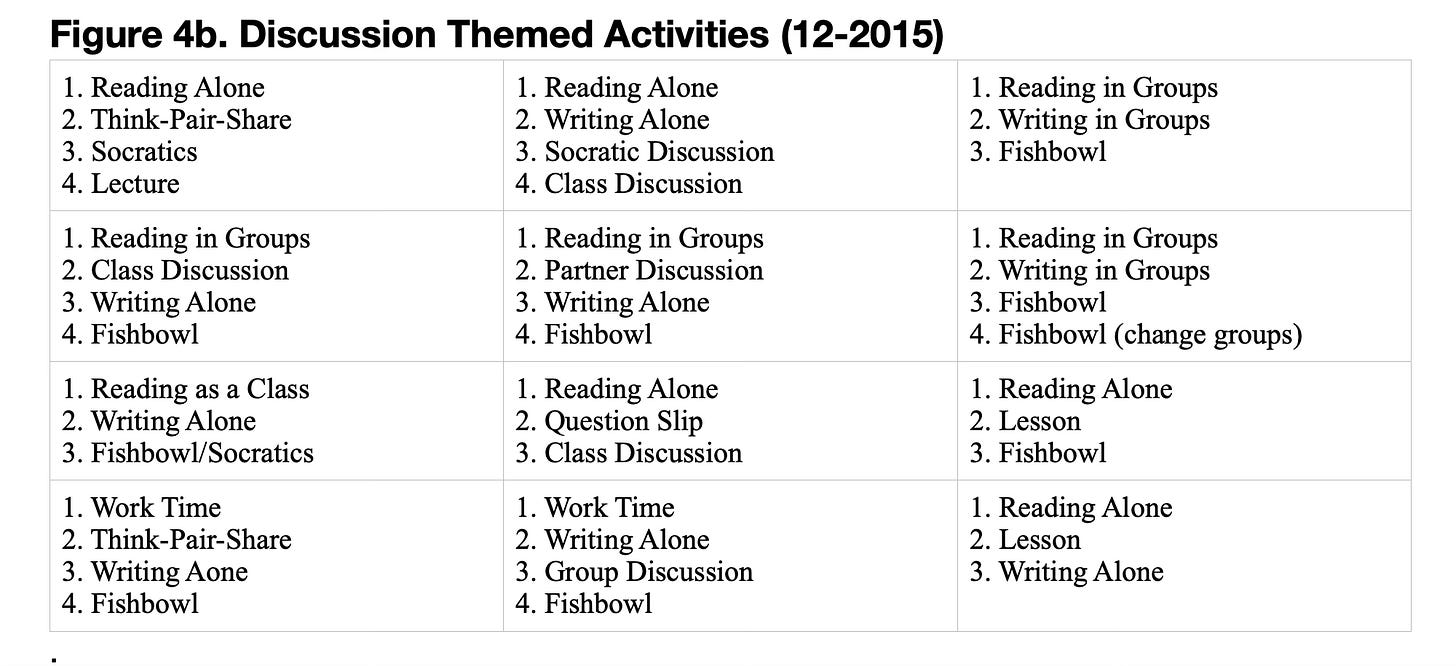

My first attempts kept the general categories, but I soon began experimenting around specific teaching activities. For example, I added specific discussion-based activities like Think-Pair-Shares and Socratic (Fishbowl) discussions.

What if students wrote first, talked to partners, and then moved to Socratic discussions?

What if they talked to partners first, reflected next, and then moved to Socratic discussions?

What if opinions changed? What if they reflected both before and after?

Here's an example from 2015.

Figure 4b. Discussion Themed Activities (12-2015)

If purpose represented nouns, then I had pages and pages of verbs.

I stopped again. Just hours before my starting point was recall. Then it shifted to sequencing. And now it was a catalogue. Had the thought experiment really been that easy?

Note: This wasn't as simple as "Write 100 example lesson plans." Since I couldn't describe my own steps, narrating the process would have proven difficult. But narrating the steps and moving from possibilities to catalogues simplified things.

Zooming out, since I used repeating weekly formats at the time (Tuesdays as Language Days, Wednesday Work Days), I sketched a simple calendar and toyed with weekly formats. Just seeing the templates gave newfound freedom.

Figure 5. Chart: Weekly Activities

However, I realized a limitation: Purpose constricts novel sequences. My favorite “days” featured novel activity sequences, juxtaposing unrelated activities. If scores of purposeful plans helped my creativity, then random plans provided both easy starters and creativity jolt-ers. But purposely being random proved exhausting. What if a computer program could generate random plans for sheer creativity?

Aside: This was 2013 or 2014, and it wasn’t until 2022, for something completely unrelated, that I realized Microsoft Excel could randomize information from a list. See my post “101 Random Lesson Plans” for more. These days, when problem solving, I love defining parameters and beginning with vast, randomized lists. If you’re familiar with ThinkerToys, if Brute Think forces connections, then randomized lists qualify, right?

Interlude: Starting with Endings

As my first semester of teaching finally ended, variety became a speed bump. My crisis of creativity shifted to a crisis of classroom management. Spoiler: I ignored the warning not to become friends with the students. So I crashed and burned like a dumpster fire for the next ninety days. (Dreaming of that first year qualifies as a nightmare!)

Aside: Regarding classroom management, two books became indispensable during year two: The First Days of School and Fred Jones Tools for Teaching. In short, set routines and clear expectations.

For the next four years, I planned with templates instead of blank pages. This drastically reduced my planning time but shifted my efforts elsewhere. “If you write it more than twice,” I’d catch myself saying, “make a template.” So I created templates for unit planning, adapting books, assignments, rubrics—you name it! But I’ll save the autobiography.

Do I still use these lesson planning catalogues now? Eh. My recipes became references. I moved from pattern to precedent. A decade after my thought experiment, I prefer “binders” and random patterns as starters.

All that said, two questions remain: So what? Who cares?

🔮 Next Time: As I sketch the post script, I'm musing on starting careers with catalogues. What if colleges ditched the stereotypical fifteen page lesson plan? What if students began with a magazine-like book of lesson templates? What if lesson planning were like trying new recipes? What if students evaluated lesson plans like Math problems? And what if a game could teach the same concept?

Hint: My next post will include a printable game as proof of concept. And since I'm talking books, I suppose it's either a book or a Masters Thesis proposal. Whichever.

New to the blog? Explore some other favorites!

✏️ Need a place to start? Check out my ongoing series, Teach Writing Tomorrow.

📓 Want other tips for teaching writing? Check out some fan favorites.

🏆 And here are some other popular posts:

🗞️ Crave honest education news? Check out same satire from The Honest School Times.

![🎲 Three Cards to Chaos: A Lesson Planning Card Game [+ Download]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!JHGu!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F91c66007-86e9-41dd-ab2c-a394cb93565f_3024x3024.heic)