🎲 Three Cards to Chaos: A Lesson Planning Card Game [+ Download]

What if teachers learned to lesson plan through a card game and a cookbook?

In my posts "Teaching & Habitual Re-Creation" and "How to Lesson Plan Once (And Never Again)," I presented shortcomings in teacher's education. How it fails to prepare. And maybe how it can't prepare. After all, no program can anticipate every teaching situation.

As I ended last time, I posed several questions: What if colleges ditched the stereotypical fifteen page lesson plan? What if students began with a magazine-like book of lesson templates? What if lesson planning were like trying new recipes? What if students evaluated lesson plans like Math problems? ("Why won't this particular lesson work?")

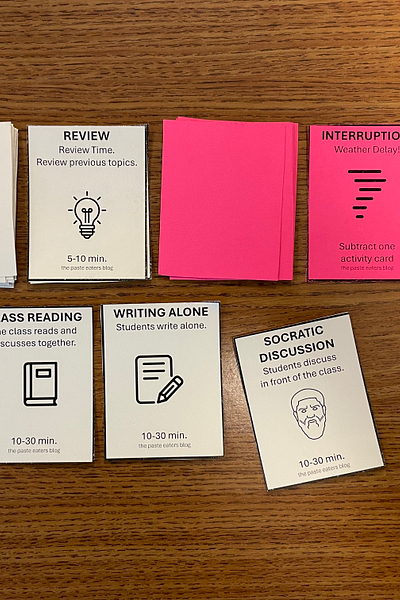

But as I narrated my thought experiment, I mused about memory as reaching into our minds for playing cards. Then I wondered: What if teaching activities were cards? What if future teachers drew activities and arranged hands into the best lesson possible? What if they drew interruptions and adjusted in real time?

However, rather than retread the formal and systematic, imagination required something different. So read and pretend and maybe play along. Here’s a brief outline:

Dialogue 1: Introducing Three Cards to Chaos.

Download and Disclaimers

Dialogue 2: A Lesson Planning Cookbook.

Teacher’s Training as Fan Fiction

🎓 Since the intended audience includes new and future teachers, I would love to collaborate with teacher’s training programs!

Dialogue 1: Introducing Three Cards to Chaos

[Early fall. As fresh sunshine streams through the second story windows, students file through the door. A mower hums nearby, spitting emerald glass, still wet from the morning dew. Leaves sway in the breeze outside the window.]

Professor: Alright, class, get out your card decks. We're going to start with a few rounds of Three Cards to Chaos today.

Elliot: What will we be planning today?

Professor: English. [Clicks and a poem fills the screen.] An Emily Dickinson poem. [The class nods.] I'll give you a minute or two to read through it first.

Elliot: What are the rules again?

Professor: You will draw five cards, arrange a lesson (or hand), then discard two.

Elliot: Do we draw an interruption card now?

Professor: Not yet. So go ahead, read the poem, draw your cards, and I'll give you a five minutes before we regroup. [Five minutes pass. The students read and deal cards.] Alright, I want to hear from three volunteers. List your cards and explain the lesson.

Jocelyn: I drew Reading in Partners, Acting a Scene, then Writing as a Class.

Professor: Why would they act before the discussion?

Jocelyn: Acting means understanding what happened. So acting helps comprehension before writing, right?

Professor: Great! Next?

Imani: Mine wasn't as exciting. I had Silent Reading, Writing Alone, then Writing in Groups.

Professor: That might sound tough. What stands out?

Imani: Well, students would need multiple prompts, right? [The Professor nods.] So maybe they write reactions first? I'm not sure what goes after.

Professor: Remember, there's more to writing than reacting. Would anyone else have suggestions? What comes before analysis?

Elliot: What if the second prompt summarized the poem? Or maybe interpreted it?

Professor: Good! I need one more volunteer.

Otis: I got Reading as a Class, Writing Alone, and Socratic Discussion.

Professor: Why would that work?

Otis: So they start by reading together. Writing before the Socratic Discussion would help them focus ideas.

Professor: Let's pretend you drew two Writing Alone cards. What if we repeated it last?

Otis: Would students compare different opinions about the poem from the discussion?

Professor: Exactly! Now everyone draw an interruption card. [Some students groan while others cheer.] What do you have to deal with?

Otis: Oh no! I drew a Weather Delay.

Professor: How does that influence your lesson?

Otis: It says to remove one card. That might mean no Socratic discussion. Or at least a short one.

Professor: And what if you had to push it off to the next day?

Otis: That means something else gets moved.

Professor: And what if you planned every day solid?

Otis: Would that throw off the entire week?

Professor: It would. Anyone else?

Elliot: Mine said Fire Drill. Discard one card from the hand.

Professor: And that's the way it will go. Now that we've warmed up, get out your books...

Download and Disclaimers

This iteration aimed for the minimal viable product, creating the fewest cards for functional gameplay. This meant ignoring numerous possibilities. Please, please, please leave comments and suggestions, but read my own questions first.

1. Other Subjects. What's a reasonable deck size? Why not expand to other subjects? Should other subjects be expansion packs? What activities are truly subject-specific?

2. Generalist Potential. What if all teachers began training for all subjects? What activities apply to all subjects? What if specialization comes later (with expansions)?

3. Limited Activities. This deck contained the most general activity categories. Many, such as Writing Alone, represents dozens of possible activities. What categories did I miss?

4. Infinite Expansion (Science of...). Why not include evidence-based activities from The Sciences of Learning and Reading? (E.g., Review becomes Retrieval Practice.) Maybe generative learning frameworks?

5. Limited Interruptions. How many interruptions are too many? Why not include more creative or serious interruptions? Why not draw multiples?

6. Limited Gameplay. Why not include dice? Why not expand to roleplaying potential? Why not plan for multiple lessons?

7. Selecting Topics. How should lesson topics be chosen? (Dialogue 2 addresses this through proposing a general high school syllabus.)

Want to experiment with your own cards? Just halve an average notecard!

Dialogue 2: A Lesson Planning Cookbook

If Three Cards to Chaos teaches lesson planning through play, this complementary volume explores planning through subject outlines and lesson plan templates. Think cookbook. All first year teachers would receive this book.

[A] Student: Professor, I don't understand this lesson planning book. Why does it start with a syllabus of high school itself? Why offer lesson plan steps without titles?

Professor: It's all about direction—of suggesting major topics you could teach. So what topics make Algebra or American History? Biology or British Literature? This syllabus outlines subjects like an atlas while lesson plans work as itineraries.

Student: Will we teach these topics verbatim someday?

Professor: Not exactly. This list isn't prescriptive, definitive, or canon. What will you teach someday? Nobody knows. This syllabus just paints big pictures.

[B] Student: What about the lesson plan section? Why explain teaching through cooking?

Professor: Pretend I've never seen a cookbook. What do they do?

Student: Cookbooks catalogue recipes and recipes list ingredients and steps. You buy cookbooks to learn how to cook.

Professor: Imagine starting with the blank page. Why recreate common recipes from scratch?

Student: I still don't understand. How does that connect to planning? I want to write my own lesson plans. Doesn't this just discourage creativity?

Professor: Not at all. In fact, this book should inspire creativity. Nothing limits anything here. Creativity doesn't always mean symphonies from nothing, but often altering or rearranging common conventions. Have you ever changed a recipe?

Student: Of course. I add and remove things all the time. Make it my own.

Professor: When do you stop using recipes?

Student: Once I know the steps.

Professor: So recipes begin as starting points but become guides?

Student: Yes.

Professor: Then read this teaching book like a cookbook: Find a recipe. Try it out. Then reflect. Start with the starting points until the recipes become references. Experience allows us to start from scratch.

Student: How could anyone write something like this?

Professor: This blends several thinking tools. Have you heard of brute force problem solving or the 80-20 Rule (Pareto principle)?

Student: I don't think so.

Professor: Brute force programs break computer passwords by methodically and systematically creating every possible combination—within a set range, of course. Brute forcing eats time, even for computers. As a fun case, several years ago some musician slash lawyers tried brute forcing—and copyrighting—every possible melody. It was a fun thought experiment.

Student: That's crazy. What about the 80-20 Rule?

Professor: Paraphrased, the 80-20 Rule says that 80% of effects come from 20% of causes. Think Frequently Asked Questions: A majority of questions are the same questions. Addressing those 20% of things means 80% of the work.

Student: How does that apply for planning?

Professor: Each subject has subject-specific activities: Math does Math things, English does English things, Science does Science things, and so on. Lesson planning just sequences relevant activities. It's both creative and predictable. Does that make sense?

Student: It does.

Professor: This section leans into the predictable (mechanical) aspects and shifts mental effort forwards. It creates new starting points. Rather than fill the blank page, instead adapt relevant templates. Choose, not create.

Student: I think that makes sense.

Professor: So let's say these plans sequence predictable activities. Sometimes the same steps apply to many topics. You can read and discuss many stories. But variations—switching or moving activities—form different lesson plans. You can read, write, then discuss a story. So same steps, different stuff and different steps, same stuff.

Student: That makes sense.

Professor: Let’s think 80-20: Each lesson plan has many uses. So if one plan has ten uses and ten plans have one hundred uses, then several pages have thousands of uses. These pages seem abstract, but this magazine contains volumes.

[C] Student: Oh, then I guess I had it all backwards. [Pauses.] Why does the third section scramble the second?

Professor: If lesson plans contain conventional associations, this section seeks novel associations. It's a creativity booster.

Student: How does that work?

Professor: Try a word problem: What two words come after January?

Student: February and March. They're months.

Professor: Good. Some things naturally follow, like discussion after reading, but others don't.

Student: So instead of January to February, January to chicken?

Professor: [Laughs.] Not quite. But random associations bend towards novelty.

Student: How would you even read them?

Professor: Normally we'd read left to right. Here you'd read any which way: down to up, right to left, and diagonally. Look for things you'd otherwise never connect.

Student: That's unique…

Teacher’s Training as Fan Fiction

As a teacher, I can only speak for my own little carpet square. Voice my own experiences. This applies to my training as well. However, after so many years at the ground level, talking others pieces together a wider picture.

I get the why behind the stereotypical college lesson plan: Length accounts for missing context. Saying the invisible parts: What grade? What skill level? What activities? What standards? What will you say? What assessments? What extension activities? And so on.

But the stereotypical college lesson plan isn't quantity versus quality. It's relevance versus irrelevance. For starters, nobody writes 10+ page lessons for 180 contractual teaching days. Students study teaching without actually teaching. Many essays here function like fan fiction. Like writing travel blogs about places you've never been.

If comprehension relies on background knowledge, some living goes before learning. This explains why my training gained relevance after teaching. Not before.

So I'll say it again: Being a student of teaching isn't being a teacher of students. Teaching teaches teachers to teach. All else is studying school.

Teachers either stumble through on the job learning—or they quit. And considering many teachers teach, grade, and go home, relevant knowledge just floats on a vast ocean of folk wisdom. Lost like foamy flotsam. Unrecorded.

Yet others fake entire careers by reading scripts. You know, The Chinese Room applied to schooling. Content knowledge isn't just irrelevant, but dangerous if it means asking questions. Just follow the canned curriculum... with fidelity. Follow the pacing guide. Use the slides. Ask the prescribed questions. Use the answer key. Never question the corporate talking points.

In the meantime, relevant training isn't impossible. Or costly. What if teaching programs acted like Rosetta Stone between colleges and K12? What if professors engaged in meta-teaching and narrated logistics to a fault? What if students translated college syllabi to basic lesson plans? What if professors narrated how they created courses?

But I suppose that’s another post entirely.

💬 Until then, what do you think about this card game and cookbook? Useful? Crazy? Let me know in the comments section.

🔮 Next time I might publish 100+ MORE Random Lesson Plans. (I’ve just been sitting on them for a while.) And in the future, I'd love to publish 100 Actual Lesson Plan Templates, like my imagined book describes.

New to the blog? Explore some other favorites!

✏️ Need a place to start? Check out my ongoing series, Teach Writing Tomorrow.

📓 Want other tips for teaching writing? Check out some fan favorites.

🏆 And here are some other popular posts:

🗞️ Crave honest education news? Check out same satire from The Honest School Times.

What a fun way to think about planning a lesson. I have several similar stacks of cards on my desks....for facilitation of meetings, strategies for leadership, etc...why not a concrete way to think about a lesson. Teachers seem to come to us with experiences from their programs that either taught them lengthy lesson plans or none at all. The result is the same, they struggle with how to plan a lesson. How can we make the transition into a teaching career easier and more successful? With ideas like this.