✏️ Getting Difficult Students to Write (and Other Topics)

Hint: It does not involve paragraph acronyms or writing mnemonics.

Last month I presented my talk “Help! I don’t know how to teach writing!” at AMLE25 in Indianapolis. The talk featured a great venue, a great crowd, and great questions. However, despite regularly speaking at conferences, I didn’t leave enough time for Q&A. Luckily I had a Google Form to capture questions as time ran short.

If you missed my talk, check out my matching post:

In the meantime, I’ve been adjusting to life with two under two. Parental leave came and went, and I landed back at school as the semester crescendos to a climax with final exams. Since then I’ve never forgotten the audience questions, but have spent time mulling them over. This post (and others) will answer those questions with more thought, although I suspect I’ll likely rewrite them further down the line.

What did audience members want to know? I’ll post the questions below and mark which ones I’m addressing today:

✅ 1. What strategies would you suggest for students who run out the clock and refuse to produce unless you spoon feed them?

2. How do you model making mistakes in writing?

3. How do you practically teach reading and writing together in your classroom?

✅ 4. What is the best way to motivate students to write?

5. What type of writing do students like or connect with the most?

6. How would you integrate writing in other disciplines?

✅ 7. What were those books you mentioned?

8. How do you integrate vocabulary into writing?

✅ 9. How do you help students who do the bare minimum?

10. How do you make writing social rather than solitary?

✅ 11. How do you preview and review topics in daily journals?

12. How do you handle students with significant learning challenges?

13. How do you handle everyone reading everyone?

14. I know teaching is a continuous process. How long did it take you to develop classroom staples and routines? Did you have any big fails you remember consistently?

This post will address a swath of questions by grouping some together and addressing underlying themes.

1. My Favorite Books for Teaching Writing

#7: What books did you mention [about teaching writing]?

The following list includes my favorite books for teaching writing. Aside from Teaching the Universe of Discourse, the rest are listed in no particular order. At some point I’ll expand this list into a full-blown post.

⭐️ Teaching the Universe of Discourse (James Moffett)

Leveled Text-Dependent Question Stems (Debra J. Housel)

They Say, I Say (Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein)

The Writing Template Book (Kevin B. King and Ann Johns)

Advanced Academic Writing / Opus 40 (Michael Clay Thompson)

Purposeful Conferences--Powerful Writing!: Strategies, Tips, And Teacher-Student Dialogues That Really Help Kids Improve Their Writing (Marilyn Pryle)

Writing Workshop in Middle School: What You Need to Really Make It Work in the Time You’ve Got (Marilyn Pryle)

Using Benchmark Papers to Teach Writing with the Traits, Grades 6 to 8 (Ruth Culham)

The Writer’s Practice (John Warner)

Roots in the Sawdust: Writing to Learn Across the Disciplines (Anne Ruggles Gere)

2. Daily Journals: Getting Started

#11. How do you preview and review topics in daily journals?

If you’re curious about daily writing, check out my early 2025 series which includes a general description, example policies, example scripts, and 50+ journal starters. While the next section points back here, I wanted to group my resources together first.

3. Writing with Difficult Students (Write Every Day)

#1. What strategies would you suggest for students who run out the clock and refuse to produce unless you spoon feed them? #4. What is the best way to motivate students to write? #9. How do you help students who do the bare minimum?

I often joke: If I could answer some questions, I could retire tomorrow. And writing with difficult students fits the bill. So how do you deal with difficult students? Each student has their reasons. I grouped these questions together for ease, but suspect the underlying nuances might require several solid attempts to answer.

To start, I want to meander around the topics before musing about potential answers.

Why do some student refuse to write? Why do some require hand holding? Why do some students prefer the bare minimum?

Consider character: Some students will always refuse. No matter what. Human nature says they didn’t opt-in to schooling, so opting out feels like their only real choice. And no matter how much we beg and barter, coax and cajole, no hippie-hippie PBIS nonsense will address this fundamental friction with human nature.

Some students require hand holding because their dispositions demand it. But this skews both directions. When students who struggle demand 1:1 attention, teachers complain. Yet when students who excel demand 1:1 attention, we write them off as needy. So we excuse one but not the other.

Some students refuse help while others jump through the cracks. They don’t want help. Again, disposition matters. Some students—despite grades as feedback—genuinely don’t think they need it. Then again, maybe others complete the bare minimum because they’re too afraid or proud to ask for help. It’s not always malicious.

Consider reading: Scarborough’s Rope suggests reading isn’t one thing. Singular reading “numbers” betray basic complexity. Some struggle with decoding while others struggle with comprehension. Some have lower vocabularies while others have poor working memories. Some read and move on without enough self-awareness to stop and reread.

Let’s look elsewhere for inspiration, thinking to mechanics and exercise science.

What if the problem isn’t the problem? My dad has been a mechanic and repairman for decades. Despite not inheriting his skills, he still impressed key troubleshooting advice: Sometimes what we see and hear isn’t the problem. Sometimes we see effects, not causes. Sometimes problems lie deeper and require disassembly. Assumptions need checked.

What if the main lift isn’t the issue? Squat University, one of my favorite YouTube channels, explains how certain weaknesses create imbalances and cause problems. Many lifting problems isolate muscles (like academic standards) yet ignore the body-as-system. You cannot address complex systems on a purely part-by-part basis.

As I’ve written elsewhere, writing instruction begins with category errors. Academic standards distort part-whole relationships and fundamentally overcomplicate the act of writing. Between terrible standards and terrible textbooks, if The Purpose of the System is What It Does, then academic standards exist to prevent language development.

So how do you help difficult students? I’ll start sketching an answer. But let’s talk running first.

Many students refuse to write because writing isn’t routine. And where there isn’t routine, resistance fills the vacuum. I liken most approaches to forcing 5K’s while neglecting the running. Rather than build endurance first, we force the action and then wonder why teachers and students alike hate it.

I hated running growing up. Despite being an All-American in Swimming, despite my above average athletic ability, I was slow. In gym I’d often be picked last because apparently the bigger kids were faster. And so it went. I didn’t run because I was bad at running. But little did I realize I was bad at running precisely because I didn’t run.

After getting married, my wife and I went on several runs. Since I flew past her, she encouraged me to start running on my own. I protested. Why would I? I was terrible at it. She then gave me the look and said being terrible never stopped her. And so I tried.

Those initial runs were painful, terrible events. I’d start and I’d stop and I’d walk. Then I’d try again. People flew past on the trails. Yet I kept persisting. Eventually I ran a mile for the first time ever without stopping. Then one mile became two and two became three and so on. Over two years, I eventually hit six nearly continuous miles. (Pesky stoplights!)

The lesson? I was bad at running because I did not run. Was I slow? Of course! But avoiding running never helped build running endurance. Truthfully, if not for plantar fasciitis and having children, I’d still be out there running four or five miles most days after school. (I haven’t quite replaced running as my daily routine.)

Let’s translate this to writing: Teachers and students alike struggle to write precisely because they do not write. The end. You may as well never exercise because you’re out of shape. And while that sounds terrible, it’s the default. I’ve rarely met teachers who outright say their students write little, but the results are obvious.

How do you write more? It’s simple: Start with the first five minutes.

Trade resistance for routine. Improving writing doesn’t require fancy programs, charts, or jargon. It likewise doesn’t require expensive consultants, thick books, or computer programs. You’d be shocked how far five minutes, a notebook, and a great question go. Start every class by writing. Make writing as common as desks and breathing.

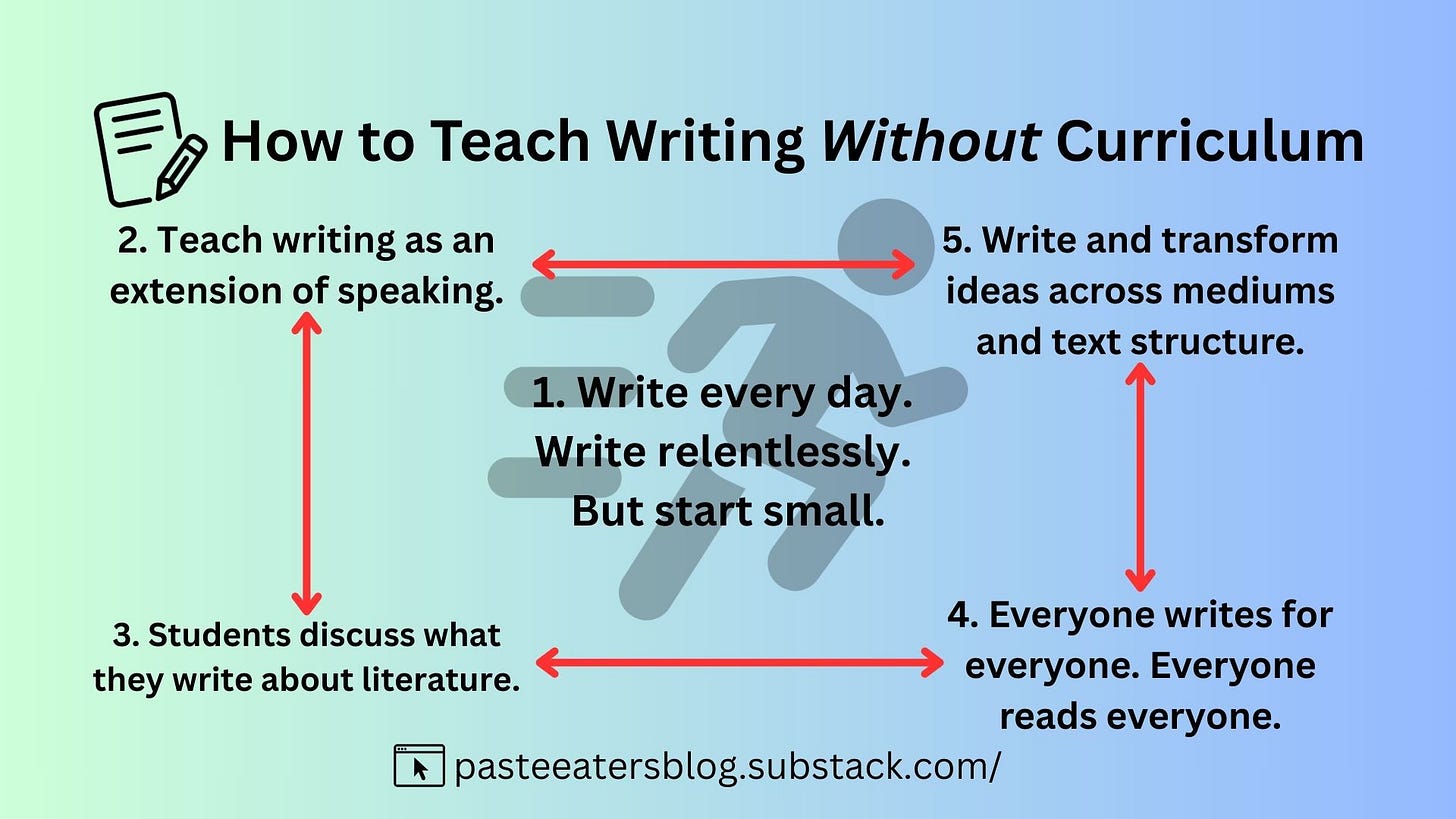

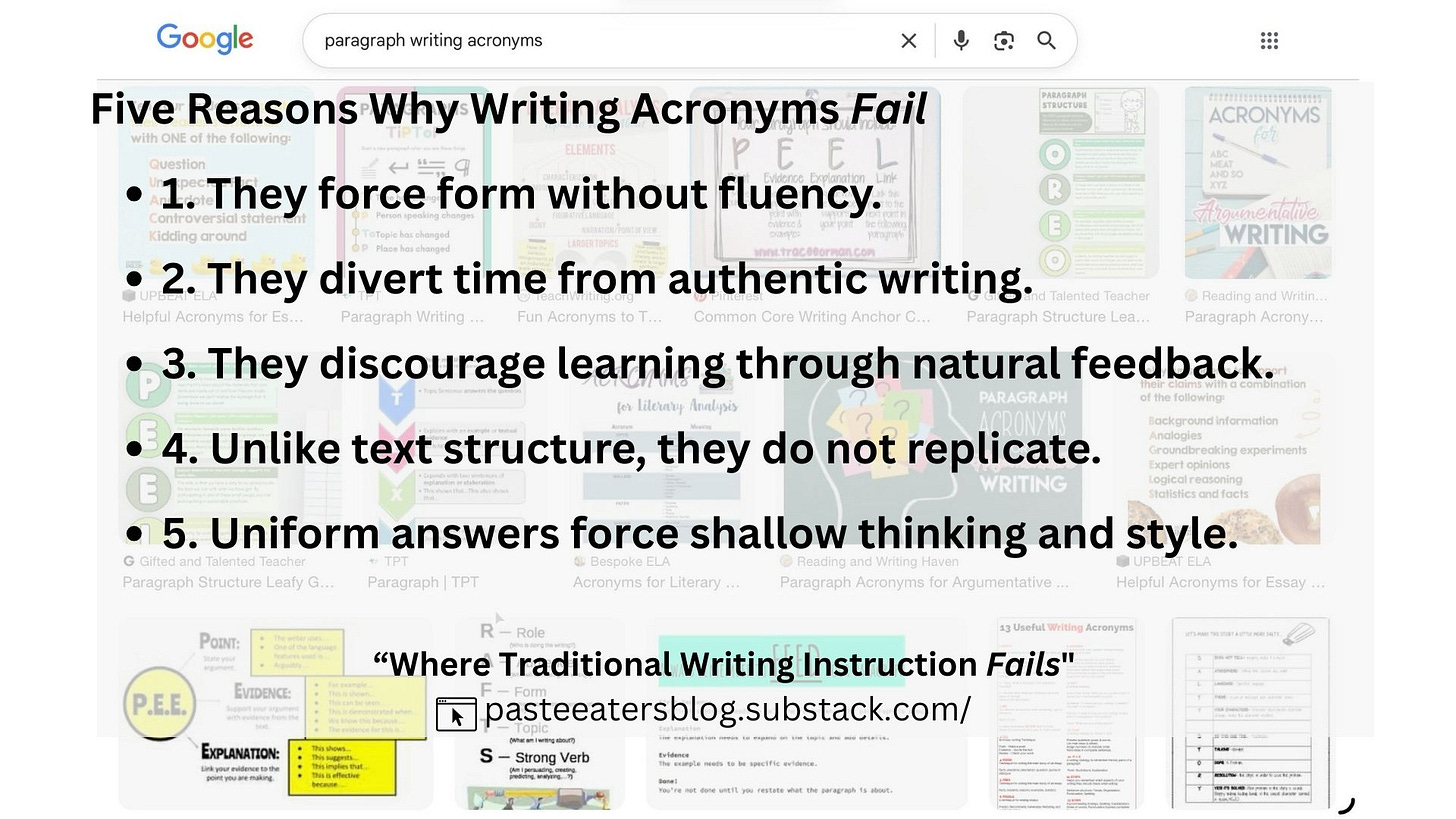

The basic procedure requires a shift in mindsets and routine. Students write for the first five or so minutes each class. And avoid the no good, terrible writing acronyms. Drop ‘em! Instead, write about literature and life. Students should preview future topics, review past topics, and write about current or calendar-driven topics.

Along the way give routine open-ended topics. Let them write about things that matter to them, including trucks, farming, the NFL, band competitions, anime, make up, and so on. It doesn’t matter if we find their self-chosen topics stupid. Writing about what matters builds meaning. If we don’t welcome writing for meaning, we close it instead.

Our so-called difficult students struggle for the same reason everyone else does: Atrophy. Because many students only ever write with acronyms and five paragraph structures, they’ve never learned to write in the first place. Oh, they follow the motions alright, but it’s like painting-by-the-colors rather than beginning from the blank canvas.

I normally dismiss many student concerns because of laziness, but with writing mnemonics I get it: Kids resist them because they are genuinely terrible.

Many teachers justify acronyms because the structure encourages writing more. Yet in conversations, acronyms encourage writing less. For many, the acronyms become destination. Teachers force form before fluency. They actively prevent learning through feedback in authentic tasks.

As I’ve written elsewhere, if you want students to write more then simply write more.

Why does writing every day work? It’s all about form and fluency.

Form refers to structure. Text structure helps both composition and comprehension. Most questions imply arrangement: topical, chronological, compare and contrast, cause and effect, and so on. Once students learn these underlying structures, writing becomes jazz-like. So what about fluency?

For just a moment, imagine an artist carefully and lovingly sculpting stone. We never question the form or sculpting part: The block is just there. But fluency builds the stone, so to speak. You cannot sculpt what isn’t there. And yet how often do teachers demand proficiency where nothing exists?

As I’ve written elsewhere, our absurd devotion to academic standards is like practicing heel striking without running.

Fluency refers to your ability to just write. You cannot teach any writing without it. Fluency allows form to stick. You know, like having a block to sculpt from.

In a perfect world, I’ve love to travel to other schools and help earnest teachers with writing. But even if I did, my advice would remain consistent: Write every day.

Do I have students resist writing? Sometimes, but resistance isn’t always boisterous. Oftentimes, it’s quiet. Truth be told, routine writing shines a spotlight on some students. Consistency provides more opportunities for help. Daily writing addresses the problem at its source.

What about behavior problems? They still happen. But in nearly ten years of daily writing, they’re the exception. August means creating routine. To some extent, what we don’t punish we permit. So I narrate and remind my expectations daily. In nearly ten years, spanning hundreds and hundreds of students, I’ve had only a handful of journal-related write ups. What do I say? Check out a sample script:

“Once I start the timer, your goal will be writing four to five sentences during that time. If you finish early, wait quietly for others to finish. Even if your neighbor finishes, you should not be turned and talking.

For more, check out my daily writing notebooks starter:

In general, difficult students either bend to social pressure or quietly refuse. But if you give them the space to create meaning, writing keeps them engaged. And yes, I encourage students to write about how much they hate writing. I just tell them to use details and provide specific examples. As Palpatine would say, Ironic.

This approach works, by the way, for the same reason as the Couch to 5K approach: Increasing, regular exposure. When I teach middle school, I start at three minutes. Then four, then five, then six. When I teach high school, I throw them into seven minute, gigantic paragraph territory. Adjust duration to fit—then eventually expand—your audience.

Beyond daily writing, I have many other strategies. Some students respond to sentence stems, others respond to whole-class writing, and so on. But more often than not, so many problems stem from atrophy rather than excess.

Towards a Summary: Writing every day is not magic. Behavior problems will still exist, but building fluency across the board helps everyone. It creates the foundation for every other skill and does not require fancy programs, graphics, or charts.

Anyways, that answer went far longer than I anticipated, so I will have to split my other answers into a future post.

Resources (Links)

🎁 New to the blog? Check out my recent starter pack as well as a Google Drive Folder with FREE classroom resources! Also, The Honest School Times has your schooling satire.

⏰ Recent Posts

Where Traditional Writing Instruction Fails (11/28/2025)

My AMLE25 Talk (“Help! I don’t know how to teach writing!”) (11/15/2025)

How to Teach Writing Without Curriculum (1.0) (11/3/2025)

10 Myths about Teaching Writing (10/19/2025)

50 MORE Metaphorical Writing Prompts (10/5/2025)

The Art of the Reading Guide (9/27/2025)

Teach Computer Literacy Before AI (9/13/2025)

The Mysterious Disappearing Analogy Book (9/7/2025)

Templates for Teaching Quotations (8/30/2025)

The Joy of Teaching Siblings (8/24/2025)

How Google Forms Simplifies Data Collection (8/10/2025)

Back to School Night (8/3/2025)

33 Big Ideas to Start Your School Year (7/23/2025)

Teach Computers Before AI: A Sketch (7/21/2025)

Creative Writing Doesn’t Exist (7/17/2025)

How to Teach with Student Writing (6/25/2025)

Practice Writing Rules by Breaking Them (6/21/2025)

🏆 Fan Favorites

✏️ Teach Writing Tomorrow

📓 Other Writing Tricks

I always make writing and running analogies too!

I think an important key is to acknowledge that writing is HaRD! Even professional writers struggle (a lot). Somehow, this motivates more of my students than if I introduced a writing exercise as “easy.”