🔬 13 1/2 Evidence-Based Reading Comprehension Strategies

What does research say about reading comprehension?

The following adapts sections of an upcoming talk of the same name for the Indiana Council of Teachers of English. This talk compares Jane Oakhill's Understanding and Teaching Reading Comprehension with Natalie Wexler's The Knowledge Gap. As always, I’m hoping an active crowd will make my session more conversation than lecture.

What’s the takeaway? Research shows aspects of reading comprehension (RC) can be isolated and improved. But not everything transfers. In fact, RC skills have quick ceilings and only work like remembering to check your work in Math. Instead, building knowledge works better than teaching abstract skills, and writing should be integrated everywhere.

Why Can’t They Read?

When I first entered the classroom, I thought passion and enthusiasm could reach every student. If I loved literature, they’d love literature. But my training never considered the reality of functional illiteracy. Enthusiasm without knowledge becomes clownish.

To me, if you couldn’t read, you couldn’t read. I had never heard of “decoding” or “comprehension,” let alone interventions. Instead, when students struggled I just reread the passage and question and wondered why they couldn’t understand.

If I counted my rosters, hundreds of students moved through my room before I asked the right questions and found actual answers.

So what would I tell my first year self?

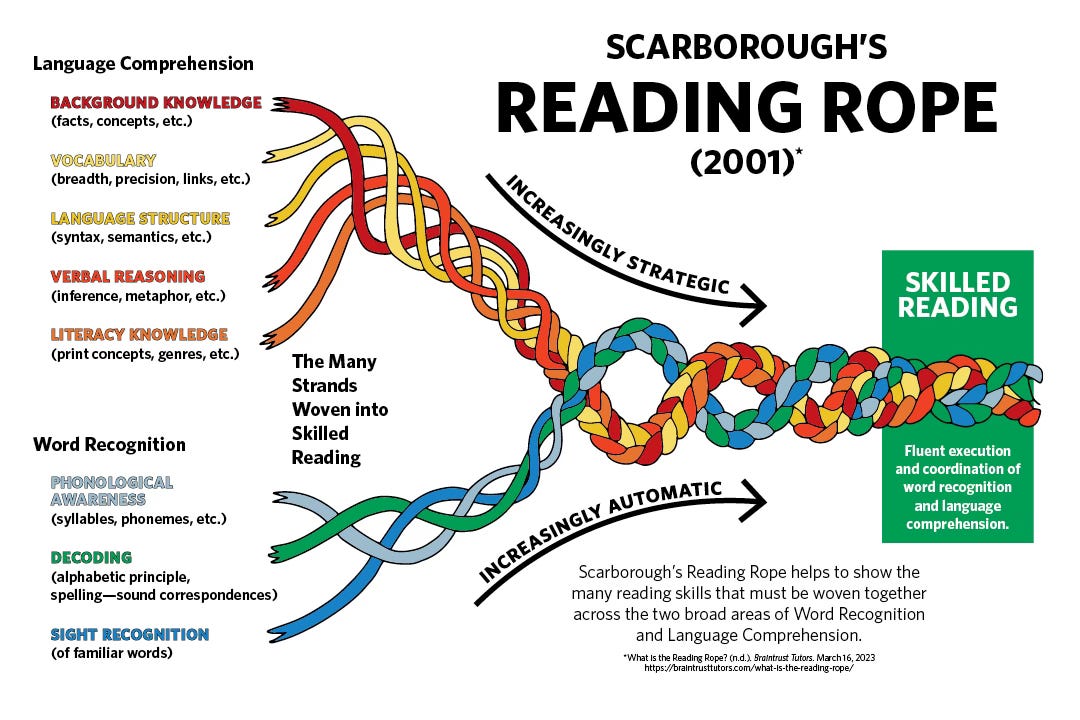

To start, I’d present The Simple View of Reading. Reading comprehension requires decoding (phonics and word recognition) and language comprehension. Afterwards I’d expand that to Scarborough’s Rope, which presents separate strands that intertwine and become automatic as readers become more fluent. See below.

And while some materials weren’t published when I started teaching, I’d suggest books like Understanding and Teaching Reading Comprehension. If you’re forced to accept convention blindly, question with research papers in hand. There are many ways to improve reading comprehension, but be careful—they have limits!

Note: When writing I’m using loose in-text citations. Also, I’ve posted my handout below:

Part I: The 13 1/2 Strategies

Strand: Inferences (Strategies #1-2)

Many students struggle to connect the dots of reading because not all dots are there. As readers, we bring information from outside the text to understand the text. For many students, poor memory (47) and lack of vocabulary or background knowledge (48-49) hold them back. So how do you help students in these cases?

Oakhill defines several kinds inferences from essential to nonessential, the former splitting to local cohesion inferences and global coherence inferences. Local cohesion inferences clarify other words “by linking them to other word and phrases in the text” (40). Global coherence inferences “connect different parts of the text by linking them within the mental model of the text” and depend on four factors: “the nature of the inference, the nature of of the text, the reading purpose, and the reader” (40). So we connect words within sentences and sentences to pages.

Strategy #1: Model inference making (50). Never underestimate the value of reading and thinking aloud. Great readers take for granted how they think when reading. Struggling readers may need help learning to think differently.

Strategy #2: Teach various inferencing questions (50). While asking comprehension questions helps clarify readings and build mental models of texts, never forget the value in students writing questions about the text. This includes several kinds:

The Journalists Questions: who, what, when, where, and why

Casual Inference Questions. What causes what? How did this cause that? (Ironically, Oakhill referenced a study and didn’t define her terms here, so I just guessed.)

Connection Questions: How does this connect to something that happened before?

My favorite resource here is the Question Answer Relationship method by Taffy Raphael. Explicitly teach students where we find answers. Having them write 20 questions about a text goes far!

However, while Oakhill develops the problem of lack of background knowledge, she leaves this thread rather loose. Part II will address this issue. Because if you ask me—or Natalie Wexler—it’s a Grand Canyon sized hole in schools and has been for decades now.

Strand: Vocabulary (#3-7)

Reading and vocabulary have a "reciprocal" relationship: The more you read, the more words you know. Oakhill refers to this as "either virtuous or vicious circles" (56). (See Stanovich's The Matthew Effect as the rich get richer.) But this works both ways: The less you read, the fewer words you know. And so when you include other issues like words with multiple meanings (55) and understanding words in degrees, not either-or (57), then vocabulary becomes a barrier to reading.

But teaching vocabulary isn't so straightforward. Oakhill admits that while we know many things about the topic, there's no best way. This bears quoting in full:

Although quite a lot is known about the importance of vocabulary to success in reading, there is relatively little empirical research onto best methods, or combinations of methods, of vocabulary instruction. Not surprisingly, it is not possible to teach children vocabulary in ways that will dramatically expand and deepen their vocabulary. The immediate results of vocabulary training are moderate, and the transfer effects to reading comprehension are smaller. (64).

She continues: "There are numerous ways to teach vocabulary, and the research base is not strong enough to form strong recommendations about which is best" (Oakhill 65). That said, what can teachers do?

Strategy #3: Just read. Volume teaches indirectly (60). The "reciprocal" relationship between reading and vocabulary cannot be overstated. In many cases we learn without direct teaching. So just read.

Strategy #4: Teach basic morphology (66). Single word parts have many applications, and mixing and matching them helps tackle more complex words "almost as if by magic" (60). Note this helps from word parts to compound words.

Strategy #5: Preview key words (64). If students will encounter unfamiliar vocabulary, then simply preview them beforehand. This will save time during reading.

Strategy #6: Teach Tier 2 vocabulary (65). This thinking splits vocabulary into three tiers: high frequency words, academic words across domains, and domain-specific words. The second tier familiarizes children with cross-domain academic words like elaborate, delicate, discern, interpret, and so on.

Strategy #7: Teach context clues (66). Modeling context clues through examples complements morphology. According to a 1998 study, teaching context clues helps “both poor and average readers” alike (66). Yet the researchers cautioned this does not necessarily transfer to overall reading comprehension.

Strand: Text Structure (#8-11)

Imagine you've only ever watched baseball your entire life and then show up to a gym on a cold Friday for a basketball game. If you ask, "What inning is this?", what would happen?

Text structure works across both fiction and nonfiction. The former includes the basic elements of fiction: setting, conflict, rising actions, the climax, falling actions, and resolution. The latter includes description, chronological, compare and contrast, and cause and effect. Truth be told, fiction can be interpreted through a nonfiction lens: stories happen chronologically as characters try to solve problems with solutions.

Yet if students have no mental models to activate, then we leave them lost and adrift as texts get larger and larger.

Aside: Oakhill, like many others, confuses text structure or organizational pattern for rhetorical mode. Purpose is not logical organization. Being “informative” does not preclude a single logical pattern. Am I the only person who sees this? Can I get an Amen?

Strategy #8: For fiction, teach the "Five Finger Trick" (90). Have students count their fingers to remember setting, character, conflict, and so on. Note that this connects to embodied cognition, generative learning, and dual coding theory.

Strategy #9: Teach signal words (74) with sentence combining (79). Some words imply other structures. If you heard first, what comes next? Teach words which imply other words and practice them through sentence combining.

Strategy #10: Highlight connecting words (79). Meanwhile, training students to pause and annotate these signal words reveals text structure over larger patterns. One study referenced showed that when signal words were highlight before a reading, everyone benefitted (79).

🏆 Strategy #11: Teach text structure (91). Teaching text structure doesn't include just the signal words or transition words, but matching graphic organizers. Oliver Caviglioli's work on dual coding theory stands out! See Dual Coding with Teachers and Organise Ideas. Joanna P. Williams has done incredible scholarship on text structure. See her summary of the field and her CATS program.

Strand: Monitoring (#12-13)

Poor readers struggle to monitor their own reading (100). Whereas good readers ask if they understand, poor readers do not. These strategies are quick, but need reminders.

The Half Strategy: Modeling (101). Never forget the value of modeling good reading skills. This skill does not come naturally to many.

Strategy #12: Regular Self-Directed Summarizing (102). Connecting back to memory, stopping to periodically summarize helps. One study highlighted how stopping to process in part helps process on the whole. Frequently stopping to summarize consciously helps with memory.

Strategy #13. Visualizing (102). As a related strategy, producing mental pictures helps retain information. This plays into dual coding theory and generative learning, which argue our brains process information through two channels: the verbal and the visual (or nonverbal). Researchers Linda Gambrell and others have proven the depths to which comprehension is tied to visualization. Programs like the Visualizing and Verbalizing by Lindamood-Bell specifically train students to process and encode information using mental pictures.

Interlude: What strategy works here?

Before continuing to Part II, read the following passage:

Shami took two wickets and spinner Axar Patel had two in two balls before captain Rohit Sharma dropped a regulation catch at slip to deny him a hat-trick.

Shami eventually broke the stand when he removed Jaker for 68, becoming the quickest man to 200 ODI wickets in terms of balls bowled in the process, and went on to complete his sixth five-wicket haul in one-day internationals.

But Gill batted with great poise in a chanceless knock, mixing stylish shots with the requisite resolve to ensure India were never truly concerned.

Which strategy works best here? If you're completely lost, I'll provide spoilers.

Part II: Knowledge Gaps

While Oakhill suggests many useful strategies, the fine print comes with a catch: Not everything transfers. Oh, you can isolate and improve general strands alright, but that doesn't mean reading improves. And what of the above passage? Despite "good" reading skills, if you know nothing about cricket, that passage may as well be gibberish.

Until I draft Part II, I want to leave you with a set of questions:

What if our literacy approach for decades has been wrong? What if focusing on skills over content has only produced declining returns?

What if reading comprehension skills have limited returns?

What if cognitive science does not support our "find the main idea" approach?

What if content unlocked nonfiction? What if students failed in nonfiction because they don't know anything about anything?

What if our teaching programs resisted advances in cognitive science? What if teachers walk onto the job knowing nothing about how we learn?

What if reading tests were just content tests?

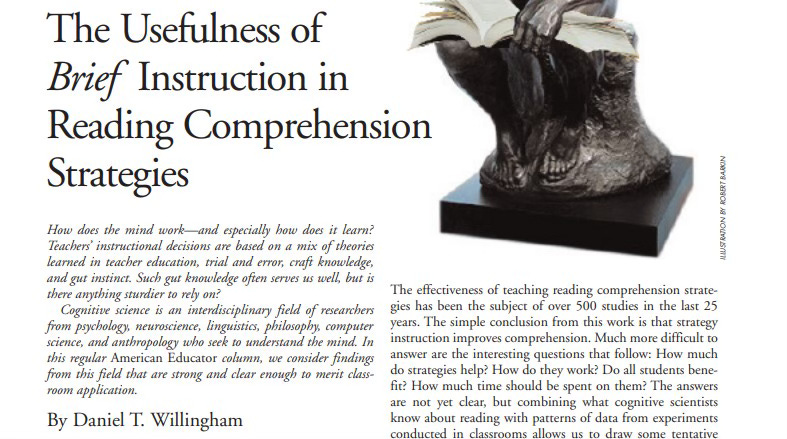

Until then, check out this wonderful piece by cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham called "The Usefulness of Brief Instruction in Reading Comprehension Strategies."

🎁 New to the blog? Check out my recent starter pack as well as a Google Drive Folder with FREE classroom resources! Also, The Honest School Times has your schooling satire.

🏆 Fan Favorites

✏️ Teach Writing Tomorrow.

📓 Other Writing Tricks

Thanks for this. What do the numbers in brackets mean?

Excellent and concise work.