🧠 Blue Trucks and Reading Dances: Five Fast Implications to Dual Coding Theory

What is the most effective reading comprehension strategy ever?*

Note: I recorded with my nearly-seven month old in the background, so you’ll hear rattles and babbling. I listened to the final mix several times through, so I hope it’s fine?

"These are very large statistical effects, perhaps among the largest ever reported in the literature of reading comprehension strategy instruction..."

In a prior post, I introduced Dual Coding Theory (DCT). DCT proposes the brain processes information through two channels: the verbal and the nonverbal. The verbal channel (logogens) processes information linearly while the nonverbal channel (imagens) processes information a-linearly.

When we experience or encode information through multiple channels, we boost working memory capacity as well as comprehension and retention. But be careful: DCT isn't just adding pictures (an oversimplification) or learning styles (a neuro-myth).

This post will explain five fast implications of DCT from Sadoski and Paivio’s book Imagery and Text. But before venturing too far, I have three quick disclaimers:

One, these implications are neither exhaustive nor the most important. Just my own ear worms. For further reading, check out Imagery and Text or Oliver Caviglioli’s Dual Coding with Teachers.

Two, while I mention studies, I’m avoiding full summaries. Depth would require full access to academic databases (my access is limited) and no concern for brevity (I’m writing for fun).

Three, despite the dual authorship, I will credit Paivio for expediency. Sorry, Sadoski: I didn’t forget you!

1. Channels Have Subsystems

While we encode information, Paivio explains, "our mental representations retain some of the original, concrete qualities of the external experiences from which they derive," meaning they are "modality specific" (29). So our mind remembers our sense experiences.

What do modality-specific encodings look like? Consider the verbal channel. We have "visual verbal encodings" (written word), "auditory verbal encodings" (spoken word), and "haptic verbal encodings" (Braille) (29-30). Verbal encodings do not exist for taste and smell. As for nonverbal encodings he just means the senses themselves plus emotions.

So does this mean the two channels have nearly ten subsystems? Apparently. But don’t overthink it. To paraphrase, we can remember how food looks without remembering taste (30).

2. We Remember Concrete Nouns

Multiple codings have an "additive" quality (73). In 1965, Paivio ran a study with thirty-two paired combinations of concrete and abstract words: concrete-concrete, concrete-abstract, and so on. If concrete words connect better to imagery than abstract words, the recall would be higher.

The results? Concrete-concrete pairings had twice the recall of abstract-abstract pairings—so "coffee-pencil" sticks easier compared to "virtue-fact" (73). This study has been replicated several times. Paivio points out, "the recall of concrete text units was much greater than abstract text units" (74).

So what vehicle ran the red light? Research says you'll remember blue truck better than just truck.

3. Definitions Need Concrete Nouns

If we remember concrete nouns better, writing with them has other implications. Paivio describes two studies where students defined five concrete and five abstract words. Concrete noun definitions had richer descriptions with shorter terms while abstract noun definitions connected to other words ("verbal-associative strategy") (110).

That said, the order of definitions matters. If you defined abstract nouns first, definitions had "fewer words" and "longer words" (110). If you defined abstract nouns second, definitions resembled concrete nouns. This basic study, he describes, has been replicated several times over.

Taken together, I wonder how two and three impact teaching writing. Can concrete nouns and definitions boost memory and reify abstract concepts in the classroom? The most hands-on application ends in the writing prompt.

4. Gestures Promote Nonverbal Coding

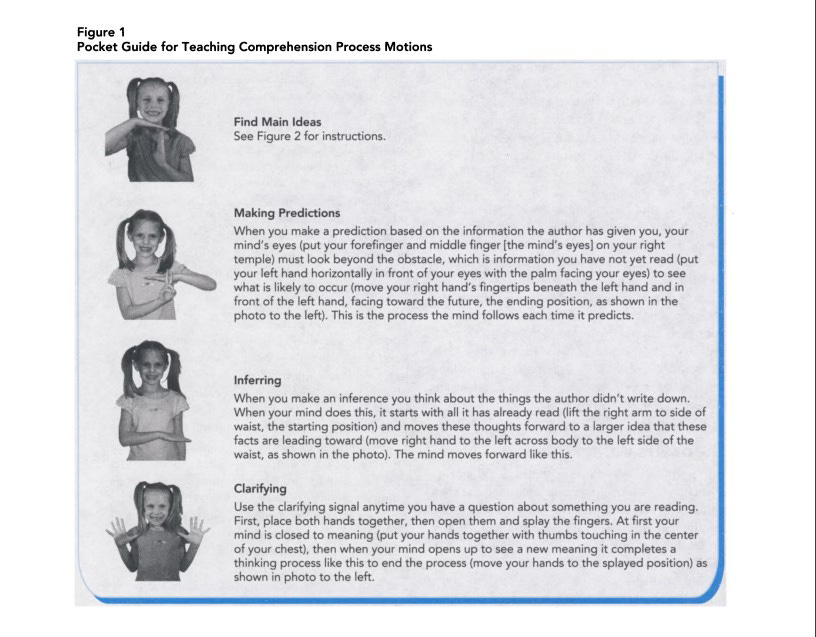

Paivio describes an intervention called Comprehension Process Motions (CPM). Under CPM, students perform hand motions that correspond to several reading moves: finding main ideas, making connections, empathizing, clarifying, and so on. So basically Sunday school dancing motions for reading?

When tested for conclusions, clarifying, and so on, those "receiving CPM instruction outperformed control subjects on each measure" (130). "Statistically," he continues, "more than 70 percent of the students' achievement was attributable to the presence of CPM instruction on each matter."

The statistical effect size from CPM was .87 or "nearly five standard deviations." As he explains, "These are very large statistical effects, perhaps among the largest ever reported in the literature of reading comprehension strategy instruction" (130).

This makes perfect sense: When I coached youth swimming, I’d explain new techniques on land instead of in the water. As children listen, they naturally mimic and move to process. If this holds true for athletics, why not academics? After all, motion explains the abacus.

That said, the statistically best comprehension strategy has limitations like a straight jacket. First, it’s audience limited. Try teaching hand motions to secondary students who hate reading. They’d laugh in your face. Second, until I find better search terms, this intervention mostly lives in academic research papers. Oh, researchers know and have known, but certainly not teachers and students tomorrow.

🔥 As a side note, how many useful interventions never exist outside research papers? This just burns me. For example, the Close Analysis of Texts With Structure (CATS) program by Williams et al explores non-fiction through text structure. But despite demonstrating such clear usefulness, it doesn’t exist elsewhere. This CATS program is a fleeting footnote. In the meantime, I’ve been slowly reverse engineering this using AI, but that’s another topic.

5. Mental Imagery is Everything

If you take one lesson from Imagery and Text, mental images underly nearly all aspects of comprehension. Paivio explains:

Mental imagery forms an important aspect of context by representing knowledge of the world. The mental connections between language and the nonverbal experience to which it refers provide concrete referents for the language and also restrict the set of images that are aroused in any given situations. (51)

But how and why teach mental imagery? Unlike other skills, the mere suggestion reads like hippie scribbles, the research papers themselves dipped in tie-dye. Turns out, mental imagery might be the most important thing we don’t teach.

As an intervention, Paivio presents seven studies, spanning younger and older audiences alike, regarding induced mental imagery. The studies themselves offered diverse applications and audiences, but the common thread went as follows: Split a class in half and teach one side about mental imagery. Test reading comprehension before and after. Every time the mental imagery group outperforms the other.

Ask yourself: Do you make mental movies while reading? I know I do. It’s only when I can’t picture information that I can’t understand it. Adults may find illustrations childish, but as Caviglioli explains in Dual Coding with Teachers, images offload and boost working memory. Let alone adding other channels like tracing diagrams, which Caviglioli explains further improves retention.

Mental imagery directly supports comprehension through activating nonverbal channels. The Science of Reading promotes automaticity in decoding, but automaticity works in comprehension as well. Both matter. As books like Understanding and Teaching Reading Comprehension argue, comprehension is complex, and students may struggle for a myriad of reasons.

Who does this work best for? Those with fantastic decoding yet poor comprehension.

If mental imagery holds true, how do you teach it? Reading the research papers as recipes, it sounds straightforward. Reading books like Visualizing and Verbalizing, you’d think only a highly structured, months-long program works. So I’m guessing it’s somewhere in between.

As of this writing, I’ve not only been drafting a post devoted to this intervention—Improving Comprehension through Imagination—but I’ve been piloting strategies during remediation time. Reciting research studies works for academic contexts, but unless these studies help kids and transform lives, they’re just printed words.

Conclusion

Whew! I originally wanted a shorter post, definitely under 800 words, but the word count sort of exploded in the edit. I love brevity, but not at the expense of clarity.

What’s the worst part of Dual Coding Theory? Discovering a half-century of research. It’s like discovering a TV show with 1,000+ episodes and not knowing where to start. But as I tell students, some problems are good problems.

In the meantime, until my next DCT post, check out generative learning, which incorporates similar ideas. I’ve reread the essay “Eight Ways to Promote Generative Learning” over and over lately!

📚 While you’re here, check out some other posts:

📱 Also, check out some other posts from my side blog, HappyCasserole.